“Interview with Ken Liu”

by Amanda Weiss

HIVEMIND Magazine spoke with Ken Liu about his piece in our February 2024 issue, “None Owns the Air,” as well as his thoughts on J.R.R. Tolkien and fantasy literature.

HIVEMIND: During our November symposium at Georgia Tech, you spoke about Tolkien’s literary intent, and especially the ways in which his work communicates pre-modern ways of thought to a modern reader. How has Tolkien’s work—his intellectual aims, his literary techniques, his storytelling style—impacted your own work?

Ken Liu: Tolkien, more than any other writer, made a claim for fantasy as a modern form. While a lot has been written about his deep engagement with premodern thought patterns and his successful effort in bringing that premodern tradition to life for modern readers, his engagement with modernity through his writing has been somewhat neglected. His defense of the “escapism” function of fantasy literature (elaborated on by Le Guin) is well-known, but worth quoting here:

Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.

J.R.R. Tolkien, “On-Fairy Stories”

Tolkien is hardly the first to use prison as a metaphor for modernity, but it’s worth pondering this passage in depth. A great deal of our discontent with modernity has been, I would argue (and I hope Tolkien will agree), due to the tendency of modernity to kill off mythologies, by which I mean the rooted, symbolic, generative stories retrieved from the collective unconscious by people from around the world, the source for all true religion, spirituality, and poetry (paraphrasing Le Guin here again). That is the Reality outside the walls of propaganda and the bars of ideology. While modernity around the world has tended to destroy and displace indigenous mythologies with sterile doctrines, Tolkien insisted that modernity can be redeemed and restored by new stories rooted in old mythologies – this is the apology (in the old sense) of fantasy that has stuck with me and motivated me in my own work.

Tolkien casts a long shadow over fantasy literature, though his influence is often described in terms of some of the more superficial elements of his legendarium. You define your own literary aesthetic for your Dandelion Dynasty fantasy series as “silkpunk,” which has sometimes been described superficially as “Asia-influenced fantasy.” How did you come to conceptualize silkpunk? How you feel about the ways in which it has been taken up by various publications/writers? How—or does—it parallel/intersect with Tolkien’s own fantasy writing?

I’ve given a definition of silkpunk that readers can access on my web site. In essence, it’s a continuation of Tolkien’s subject of mythologizing the modern by re-rooting, re-inventing, re-appropriating, and re-purposing the indigenous. One way to think of it is as a kind of Renaissance—but applied to classical East Asian traditions instead of Greco-Roman traditions, although I’ve approached the project in a more syncretic fashion, building connections and parallels between, among others, the Greco-Roman, the Judeo-Christian, the Anglo-American, and the East Asian traditions in order to suggest alternative modernities.

Modernity shouldn’t be monolithic or sterile, but instead should be rooted in our collective mythologies. So many from around the world feel disconnected from modernity, that “tradition” and “modernity” are in conflict. The only way out of this conundrum is to construct our own new modernities with the stuff of dreams, to imagine futures grown from the deep soil of myths.

Could you tell us more about your story in this issue, “None Owns the Air,” and how it approaches fantasy as a genre? How does this piece and the Dandelion Dynasty series more broadly respond to existing fantasy traditions (inside and outside of Tolkien’s influence)?

“None Owns the Air” is set in the world of the Dandelion Dynasty series. More precisely, it’s a prequel recounting the invention of the biomechanically inspired airships that would play a prominent role in the series later.

There are two aspects of the story I want to highlight. First, there’s the emphasis on technology and invention, often neglected in fantasy. However, technology, or human craft, is an essential part of human nature, and no fantasy exploration of human nature can be complete without engagement with human craft. In “None Owns the Air,” I treat invention as a form of poetry, and the invention of the airship is no less fantastic than the composition of an epic poem.

Second, there’s an emphasis on skepticism and irreverence, a punk-inflected attitude toward tradition. This is essential in the silkpunk project since you cannot reinvent a tradition if you treat it as static. In truth, organic indigenous traditions—indeed, all vigorous traditions—are always in flux and constantly change, reinventing themselves and growing in response to a changing world, all the while holding on to the core of an animating mythology, a living constitution.

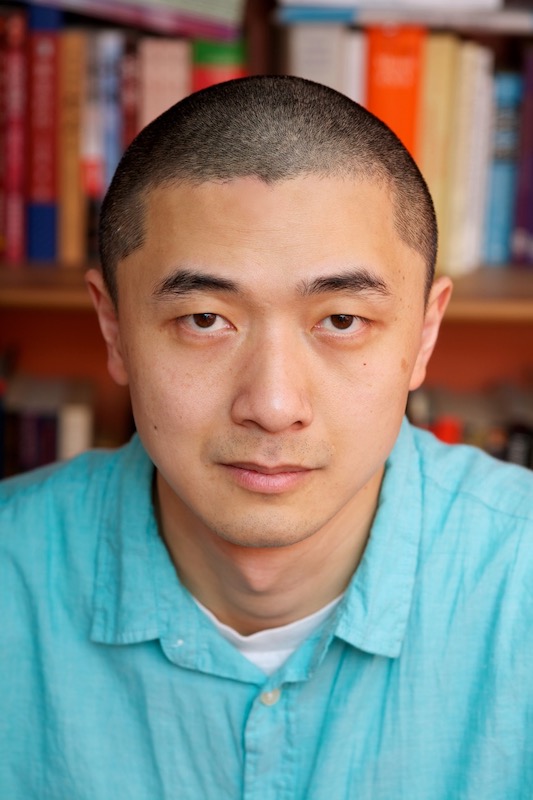

About Ken Liu

A winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, Ken Liu (http://kenliu.name) is the author of the Dandelion Dynasty, a silkpunk epic fantasy series (starting with The Grace of Kings), as well as The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories and The Hidden Girl and Other Stories.