by James C. Opperman

The wind blows in from the north, carrying with it the promise of snow. It creeps into the building no matter how often Natsuko fills the crevices in the hut she and Miyuki built all those years ago, when they moved together to the base of the mountains.

Natsuko stands at the window and watches the rumbling clouds slip lower and lower in the sky. Soon they will envelop the mountaintops, and the storm will begin in earnest. Already the air is cold, worming its way beneath her skin and settling in her bones, a guest both uninvited and inescapably familiar. She shivers, steps back into the hut, and slides the window closed. It won’t do much, but at least it will keep out the worst of the wind.

Behind her, Miyuki clatters about the kitchen, preparing the rice and dried fish for dinner. Not much, but neither of them needs much food anymore — too tiring to chew with aching jaws.

Natsuko turns and watches her wife. She is as beautiful as when they first met, as graceful, as wild. Miyuki dances around the stove, standing as far back as possible from the small fire. She uses a long pole to pluck the pot of boiling rice from the flames and rushes it to the table. Her long hair, black as the caverns underneath the mountains where it is said the gods live, is tied up in a tight bun and shines in the lamplight. Even after over fifty years together, Natsuko still feels like she doesn’t fully understand the woman who shares her home. Every day brings a new discovery, a new adventure.

That is the secret to the health of their marriage.

Natsuko crosses to the knee-high table upon which Miyuki has already placed the dried and salted snapper and settles herself on the same worn cushion she’s used for as long as she can remember. The fish smells gods-blessed, the rice as fluffy as a deer’s tail.

A finger of cold wind slides down the back of her robe to tickle her spine. She shivers again. The mood is broken.

“We should build a larger fire,” Natsuko says. The heat from the kitchen fire pit hardly reaches the table. She is too old to play games with the weather. Her fingers feel like dry bark, and they don’t cooperate as she’d like as she reaches for her chopsticks. She drops the utensils, and one of the chopsticks rolls off the table and lands in the dirt.

“You know how I feel about that,” Miyuki says as she joins Natsuko at the table. “The last thing we need is to risk setting the house ablaze.”

Miyuki stands up and retrieves another set of chopsticks from a cloth bundle in the kitchen. When she returns, she brings with her a second set of robes, this one more heavily padded and quilted with cotton. They are white, dazzlingly so, and Natsuko hesitates.

“They’ll get dirty,” she says. Miyuki ignores her, and drapes the cloth around her, tucking the edges in beneath Natsuko’s seat cushion.

“Don’t be stubborn,” she says, but the crow’s feet around her eyes dance with her smile as she does so. “This storm will be bad. I can feel it in the air. You need to keep warm.”

Miyuki, however, still wears her summer robes. They are dark, once navy but now faded with countless washings to a mottled blue-grey, and patched in places.

Her eyes sparkling, Natsuko says, “I don’t know how you can stand to be in such thin clothing in this weather.” Miyuki laughs.

“You say that every year.”

“And it’s true every year. But you’re right — this storm feels like a bad one. I can’t remember the last time it was this cold.”

But that’s not true. Natsuko can remember one night. A frigid night, moon and gods both absent, when she thought she might die. Looking into Miyuki’s eyes, she can’t believe she’s never shared this story with her wife. She uncorks the tale and begins to speak:

It was a dark night, and as I ran the ash that was raining from the sky turned to snow. I didn’t register the change, at first. All I wanted was to escape the roaring smell of burning wood and flesh, the amber glow of the flames consuming my village.

In truth, only half the village burned that night, and not everyone in the buildings that burned lost their lives to the bandits that brought the torches. But I didn’t know that. I thought everyone I’d ever known was dead. I suppose I can be forgiven that. I was a child.

As I ran, my bare feet cracked in the cold, but I only noticed when I stepped on a twig or a pebble hiding beneath the dusting of ash-covered snow. Beyond my lack of shoes, I wore nothing but my sleeping robes. My family’s house had been small, and the six of us — my mother, my father, my older sister, my two younger brothers, and me — slept huddled together in the center of the one-room house. The combined body heat meant that even in winter, none of us wore more than a thin robe. Not enough protection for a desperate flight into the mountains.

I knew they were behind me. I didn’t have to look to know. They’d seen me running away and were after me, intent on finishing whatever mission had brought them to my village.

I climbed higher and higher into the mountains. Further than I’d ever gone before, past the well-trodden paths the hunters used, past the small shrine dedicated to the guardian spirit of the mountains. I ran through moonlight and shadow and falling snowflakes the size of my hand, unsure of where I was going. I ran until my feet began to bleed into the snow.

The wooden hut took me by surprise. Someone lived there, so high up? My legs quivered. My belly ached, crying out for a rice ball like the ones my mother made. I crammed a handful of snow into my mouth, hoping it would quiet my stomach.

It did not.

I think hunger was what drove me into the hut more than anything else. By that point I was so cold I’d stopped feeling the weather’s bite, but the cramps in my gut cried out, demanding food. I circled the hut, keeping an ear and an eye out for the men who’d torched the village and another ear and eye out for any signs of life inside the building before me. Finding neither by my second pass, I slipped inside, quiet as a hare, ready to bolt once more should I see anything dangerous.

The hut was empty. It was dark inside, and I paused next to the doorway to let my eyes adjust before looking around. At one point it had probably been someone’s home, but even I could tell that it had been many moons since anyone had lived there. There was nothing there. No food, no bed, no blankets. Only a pile of rotting straw in the corner. In the dark, it looked like a sleeping bear.

It was better than nothing. My blood slowed from my mad rush away from my village, and I felt the cold storming its way into my body, hardening my muscles and locking up my joints. A layer of straw would warm me. I crawled into the pile, ignoring the scratchy feeling and urge to sneeze raw straw always gave me. It was hard to ignore the clamoring hunger, but I did my best.

Only then did I allow myself to weep for my family. I did so silently. Shivering sobs stopped in my throat, wracking my body as I cowered beneath the straw, afraid of men and beasts discovering my hiding spot and eating me.

At some point, drained and exhausted, I fell asleep.

The wind outside has graduated to a gale. It rattles the window shutters, demanding to be let in, and when it doesn’t get its way it screams its frustration into the night. Natsuko doesn’t have to look outside to know that snow has already begun to fall, a funeral shroud choking the earth beneath it.

Natsuko watches Miyuki. It’s impossible not to. She sits at the table, her back to the window and the storm. The dishes are forgotten. Miyuki hangs onto every word of the story. She fidgets as she listens, and the movement has loosened the coiled snake of her hair to the point where strands begin to slip free.

Their kettle shrieks, startling Miyuki from her trance. She shakes herself and retrieves their only teapot, a sturdy, black, inelegant thing battered just as much by time as by the smith’s hammer. She fills it with water and tea leaves, pours the concoction into a cup, hands it to Natsuko.

“Your hands are shaking,” she says. Natsuko nods. The quilted robe has warmed her core and stopped her shivering, but her hands are a different story entirely. They ache even in the relatively mild temperatures that signal the changing of the leaves; now, in the dead of winter, where the god of snow has locked the god of wind in a cage, they do more than ache. They are so cold they scream.

Natsuko says none of this. “Thank you,” she says instead.

“It’s no wonder…” Miyuki begins, but trails off. Natsuko looks at her and cocks her head. It’s unlike Miyuki not to speak her mind. Natsuko has long since learnt to wait.

“It’s no wonder you don’t like straw,” Miyuki says finally. It should be funny — it’s a funny sentiment — but it’s not. In truth, Natsuko hasn’t registered any particular dislike for straw, but now that she thinks about it, she can’t remember the last time she had much to do with it. It’s always been Miyuki that handles re-stuffing their sleeping mats or weaving new mats for their home.

Natsuko feels a renewed surge of affection for her wife. “Perhaps,” she says, smiling over her tea mug. The warmth seeps into her joints, spreading outward, settling in her blood. She feels lighter, and falls silent, enjoying the faint prickling sensation as it spreads outwards up her arms.

“Well?” Miyuki says.

“Well? Well, what?”

“What happened next?”

“Pour me another cup of tea and I’ll tell you.”

Miyuki rushes to do just that.

I couldn’t have been asleep for very long. I awoke in darkness to the sound of crunching snow outside the hut. I remember coming to in an instant, one minute dead to the world, the next wide awake, alert and tense underneath the straw.

Whoever — or whatever — was out there sounded heavy. They—or it— paced around the hut, just as I had, searching for signs of life. Once, twice, three times it circled, a hawk on the wing with a mouse in its sights. Then it went still.

Just when I thought that perhaps I was safe, the door opened.

A man stood there, silhouetted in the moonlight. I don’t know if he was one of the people who had come to my village, but like them he had a single sword strapped to his waist.

He stepped into the shack.

“Come out, little mouse.”

I sucked in a breath. I couldn’t help it. I don’t know if he heard me, or if he’d already figured out where I was, but at the sound of that breath he looked directly at the pile of straw. At me.

“Found you,” he said, and took a step towards my hiding place. Even now, I can hear the giddiness in his voice. I’d tried so hard to escape, but now there was nowhere to run.

Memory is a slippery beast. I couldn’t see his face, not with the way the moon shone from behind him, and now, through the magnifying lens of memory, I’m convinced he was a hulking ogre. But he couldn’t have been — the hut was small, and he fit comfortably inside it. But I could smell him. His scent crashed through the hut. He smelled of wild boar and deer piss, of sour sweat and unwashed clothes. I’ll never forget that smell. I remember thinking, as he drew his sword, that I’d go to the afterlife with that smell in my nose.

Perhaps that’s why I screamed. I’ll never know for certain.

All I know is that the man froze mid-stride, his sword halfway drawn from its scabbard. The scream — the kind of scream one can only make in mortal terror, the kind that can freeze rivers and shatter stone — faded. In its place, a figure stood in the doorway.

This one, though, emitted a soft glow of its own, enough that I could see her clearly.

It was a woman, and she was beautiful.

“More beautiful than me?” Miyuki asks. Natsuko rolls her eyes.

Like I said, the first thing I noticed was her beauty. She had long, straight black hair that hung down to her waist. It fanned out behind her like a phoenix’s tail. Her eyes shone, glinting like early morning dew. They were eyes to fall in love with. She wore a white robe, fastened with a white sash. Both were made of finer cloth than I’d ever seen in my entire life and were embroidered with all manner of beasts — monkeys, badgers, bears, dragons, and men — in white thread.

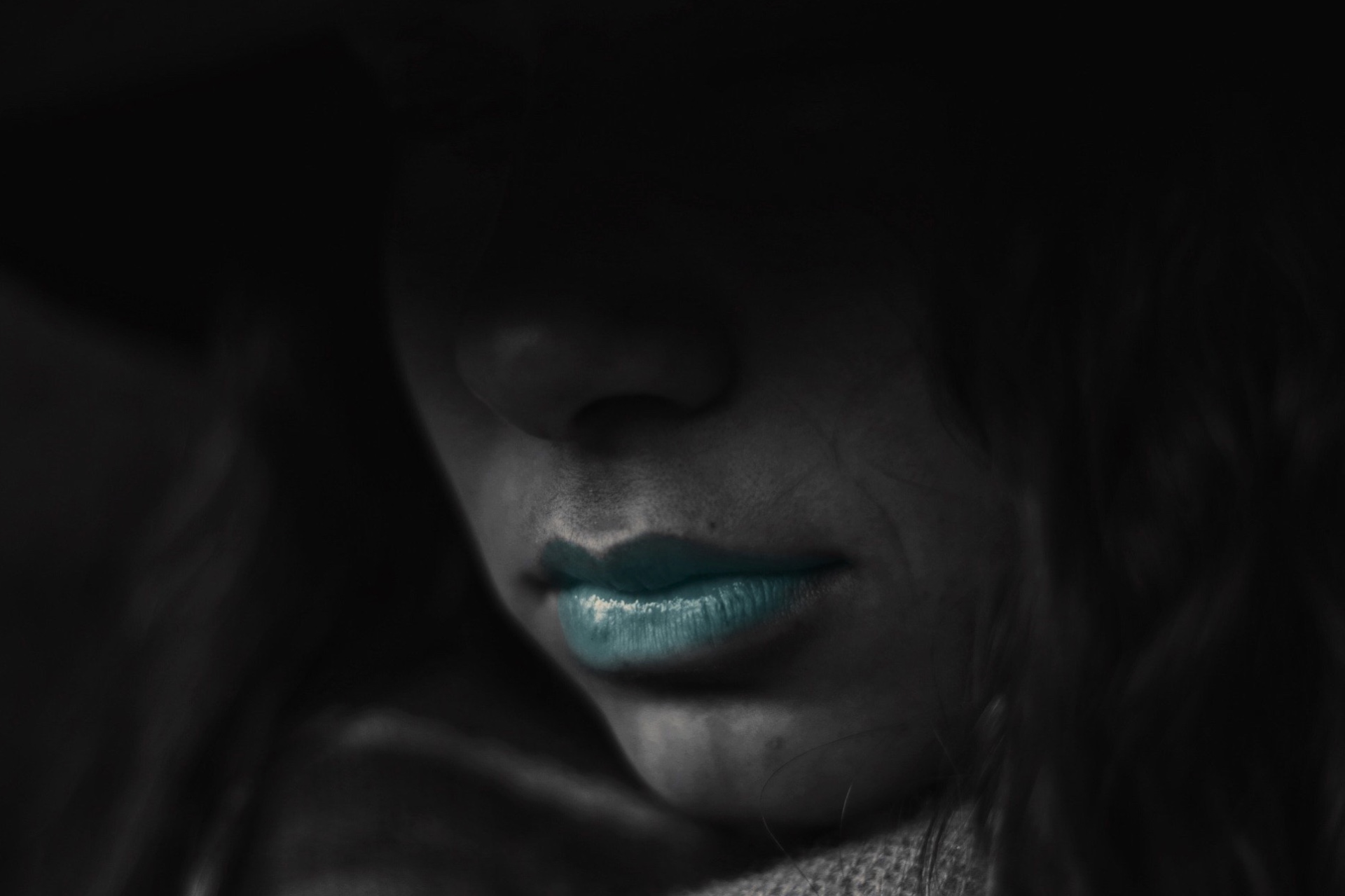

Where a normal woman’s lips would be red, hers shone a pale blue, the color of the sky after it rains and the clouds disappear. And her skin. So pale, a gorgeous, a translucent pearly white that shimmered as if you could see through it. She looked like she was made of snow.

I remember she was smiling.

She snuck up behind the man, only now unfreezing in the wake of my scream. As he finished drawing his sword, she leant forward. Her eyes flashed, her smile grew wider. And she breathed on his neck.

It was like watching a river freeze sped up a thousandfold. Ice crystalized where she breathed and spread, snaking down over his shoulders and onto his chest and arms. I saw his muscles tense as the ice overtook them, saw how his limbs locked in place, saw the patina of hoarfrost crest over his sword like fog rolling off the mountaintop.

When the ice had enveloped him completely, the woman reached out with one slender finger and touched the back of his head. The touch was gentle, almost a lover’s caress, though at the time I wouldn’t have known enough to make the comparison. But gentle as it was, it upset the ice statue’s balance, toppling it in slow motion.

When he hit the ground, the man shattered, scattering flecks of himself across the floor like broken beads from a necklace.

My would-be assailant was no more.

I let myself breathe.

Then the woman was standing over me.

“Hello, little one,” she said. Her voice shook with the tolling of temple bells and fluttered like the evening breeze. The crash of thunder and the beating of dragonflies’ wings. It was entrancing, magical. Without knowing why, I stood, brushing straw off my tattered robe in an effort to make myself look presentable. Over the woman’s shoulder, through the still open door, I could see the snow falling outside, but I didn’t feel the chill.

I didn’t know how to respond, so I did what my mother had always taught me to do whenever I met someone more important than me, which in those days was everyone. I bowed.

“Such manners,” the woman said, and she crouched down, bringing her face to my level and back into view. “What’s your name?”

I don’t know why I thought the woman’s eyes were beautiful. Up close, I could see that the irises weren’t brown, like yours or mine. They were blue — a blue so pale that they were almost white. They blended into the whites of her eyes, so it looked almost as if there were orbs of ice staring out at me from that exquisite porcelain face.

There was nothing human about those eyes.

When a spirit asks you a question, you answer. “Natsuko,” I said.

“Summer child,” the ice lady said. “A pretty name, little one, for a pretty little girl. But it doesn’t sit very well in my mouth, as I’m sure you can guess.”

I nodded, though I had no idea what that meant. As I did so, I caught a glimpse of a space on the woman’s robe on her left lapel, which up until a moment ago had been empty. Now, there was a faint outline of a man with a drawn sword appearing there, the embroidery seeming to melt upward out of the cloth. The shape solidified, and without thinking I reached out and touched it.

The robe was the coldest thing I had ever touched. Colder than snow, colder than ice. It sucked the heat right out of my hand, leaving it instantly numb. I jerked my hand back, stunned, and felt my eyes go wide. The woman laughed. Like her voice, her laugh contained multitudes. It was beautiful and horrific all at once. I longed to hear more. All too soon, however, her laughter stopped. When I raised my eyes to meet hers, careful not to raise my head too far out of my bow.

“Pretty and capable of making me laugh,” she said, but this time it sounded more like her words weren’t meant for my ears. “I guess one meal is enough for the moment.”

The woman refocused on me, her manner now different. There had been a tang of danger in the air that now dissipated, one I hadn’t even noticed until it was gone. While still alien, the woman no longer seemed predatory. The glint vanished from her eyes, and once more she appeared as lovely as a goddess. That was fitting. For all I knew, she was one. Who knows under what guises, and for what reasons, the gods stalk the realms of mortals?

“You must promise never to tell another human of what happened here tonight,” she said. If there had been any doubt left in my mind that I was speaking with a spirit, those words ripped it away. Only spirits exacted promises like that.

I nodded. What else could I do? Refuse, and be frozen like that bandit?

“Promise.”

“I promise,” I said.

“Good. I’ll be watching, little one.”

And just like that, the woman was gone, vanishing in a flurry of snowflakes that settled over the shattered corpse of the man. Left alone once more in the hut, I started to shiver. Outside, the snow continued to fall.

Silence falls in the hut. It stretches onward, like the river that rings the earth, keeping the heavens at bay. Natsuko resurfaces from the memory as if returning from a trance. Her mug is once again empty, the kettle cold. She’ll have to boil more water.

“A good story, no?” she asks, covering up a sudden sense of unease under the weight of the broken promise. “Some days, I’m not sure myself whether it actually happened. Others…” she shrugs. “I guess most days, I don’t remember it at all. It was so long ago.”

Miyuki’s eyes shine. Her hair has fallen almost completely out of the bun now, and it hangs down her back.

“You promised not to tell,” Miyuki says.

“Yes,” Natsuko says. “And for a long time, I didn’t. But this storm reminded me of that night, and suddenly I wanted to share the story with you. I know you like the old ghost stories.”

Natsuko has more to say, but she stops speaking. She’d been looking out into the halls of memory as she spoke, but now she looks at Miyuki’s face and sees it stricken with grief.

“You promised not to tell,” Miyuki says. “What have you done?”

She begins to melt. The skin Natsuko is so used to seeing runs together, the wrinkles sloughing off her face until it is once more as smooth as when they first married. Only now the skin is white, so white it is almost transparent.

And her eyes. Her eyes are no longer the deep, dark brown Natsuko so loves.

They are a pale blue.

There are fewer empty places on the white robe Miyuki wears than Natsuko remembers, but it is by no means full.

Before her sits the woman who saved her as a child. Unchanged, exactly as Natsuko pictured her when telling her story. Echoes of promises made, promises broken, slink through Natsuko’s head.

The empty mug rolls from Natsuko’s hands. Slips off the table, thuds into the dirt. There are no words for what she is witnessing happen to her wife.

She wants to scream, to let loose another one of those earth-shattering screams, like the one in the hut from so long ago. A scream to break reality, to undo time.

Instead, all she can say is, “You’re her. The spirit.”

Miyuki nods. “I told you I’d be watching.” Her blue-lipped smile is sad. Her lips purse and she inhales, a soft whistle that chills the air around her.

The woman who had once been Miyuki leans forward, as if to kiss Natsuko. Despite her terror, Natsuko instinctually leans forward, performing her half of a dance they have perfected over long years.

Air cascades from the lips of her love, washing over her in a gentle caress. Miyuki’s breath is the early morning snowfall, the howling north wind, the quiet deadness of night. Already, she can feel the chill spread, take root in the space between her heartbeats.

“Goodbye,” Miyuki says. A tear slips from her eye and freezes on her cheek. On her robe, in an empty space between a crying child and a man with an axe slung over his shoulder, a seated woman shimmers into existence.

Natsuko cannot look away. She finds she cannot move at all. By the time Miyuki slips from the door of their cottage and bursts into a swirl of snowflakes, Natsuko is lost in unseeing, frigid numbness.

The wind dies, leaving a mournful silence in its wake, broken only by the terrible sound of ice slowly, steadily melting.

Outside, the snow falls, silent and pristine and ever so beautiful.

About the Author

James C. Opperman is a speculative fiction author, software engineer, and game designer originally from South Africa, though he currently lives in New York City with his partner and their dog. When not writing, he can be found rock climbing, playing tabletop games, and dreaming up new worlds to play in. He is a 2018 graduate of the Clarion Writers’ Workshop and holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College.