This story is part of the Translating Culture collection, a multimedia showcase of folktales translated from Russian, Spanish, and Arabic, curated by Sofi Sanders. An article discussing the collection is available in the non-fiction section.

A story of pride, family, and cooperation

A chapter from South American Jungle Tales by Horacio Quiroga

In the woods near a farm lived a flock of parrots. Every morning, the parrots went and ate sweet corn in the garden of the farm. Afternoons they spent in the orange orchards eating oranges.

They always made a great to-do with their screaming and jawing; but they kept a sentinel posted on one of the tree tops to let them know if the farmer was coming.

Parrots are very much disliked by farmers in countries where parrots grow wild. They bite into an ear of corn and the rest of the ear rots when the next rain comes. Besides, parrots are very good to eat when they are nicely broiled. At least the farmers of South America think so. That is why people hunt them a great deal with shotguns.

One day the hired man on this farm managed to shoot the sentinel of the flock of parrots. The parrot fell from the tree top with a broken wing. But he made a good fight of it on the ground, biting and scratching the man several times before he was made a prisoner. You see, the man noticed that the bird was not very badly injured; and he thought he would take it home as a present for the farmer’s children.

The farmer’s wife put the broken wing in splints and tied a bandage tight around the parrot’s body. The bird sat quite still for many days, until he was entirely cured. Meanwhile he had become quite tame. The children called him Pedrito; and Pedrito learned to hold out his claw to shake hands; he liked to perch on people’s shoulders, and to tweek their ears gently with his bill.

Pedrito did not have to be kept in a cage. He spent the whole day out in the orange and eucalyptus trees in the yard of the farmhouse. He had a great time making sport of the hens when they cackled. The people of the family had tea in the afternoon, and then Pedrito would always come into the dining room and climb up with his claws and beak over the tablecloth to get his Papa. What Pedrito liked best of all was bread dipped in tea and milk.

The children talked to Pedrito so much, and he had so much to say to them, that finally he could pronounce quite a number of words in the language of people.

He could say: “Good day, Pedrito!” and “nice Papa, nice Papa”; “Papa for Pedrito!” “Papa” is the word for bread-and-milk in South America. And he said many things that he should not have; for parrots, like children, learn naughty words very easily.

On rainy days Pedrito would sit on a chair back and grumble and grumble for hours at a time. When the sun came out again he would begin to fly about screaming at the top of his voice with pleasure.

Pedrito, in short, was a very happy and a very fortunate creature. He was as free as a bird can be. At the same time he had his afternoon tea like rich people.

Now it happened that one week it rained every day and Pedrito sat indoors glum and disconsolate all the time, and saying the most bitter and unhappy things to himself. But at last one morning the sun came out bright and glorious.

Pedrito could not contain himself:

“Nice day, nice day, Pedrito!” “Nice Papa, nice Papa,” “Papa for Pedrito!” “Your paw, Pedrito!”

So he went flitting about the yard, talking gayly to himself, to the hens, to everyone, including the beautiful, splendid sun itself.

From a tree top he saw the river in the distance, a silvery, shining thread winding across the plain. And he flew off in that direction, flying, flying, flying, till he was quite tired and had to stop on a tree to rest.

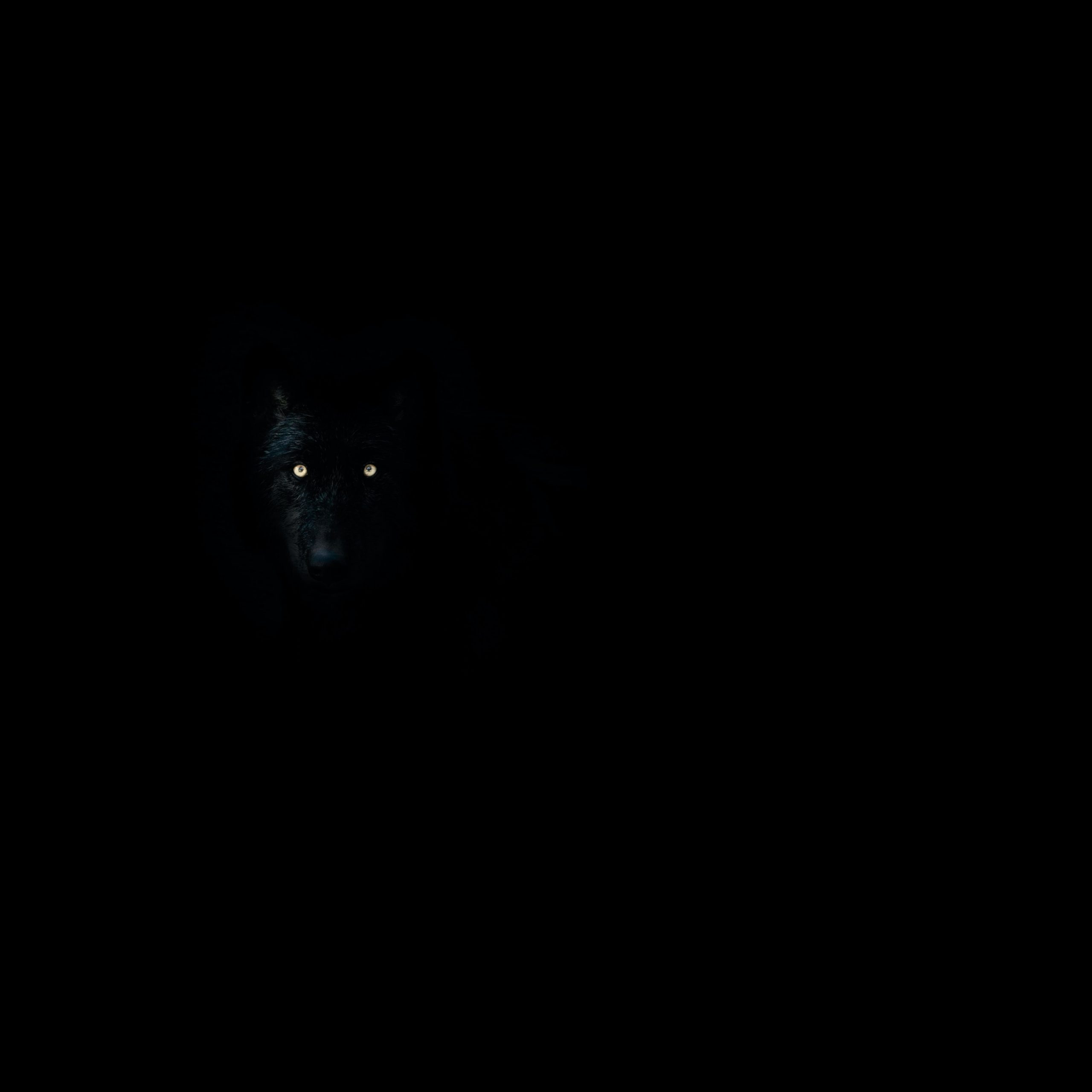

Suddenly, on the ground far under him, Pedrito saw something shining through the trees, two bright green lights, as big as overgrown lightning bugs.

“Wonder what that is?” thought Pedrito to himself. “Nice papa! Papa for Pedrito. Wonder what that is? Good day, Pedrito! Your paw, Pedrito!…”

And he chattered on, just talking nonsense, and mixing his words up so that you could scarcely have understood him. Meantime he was jumping down from branch to branch to get as close as possible to the two bright gleaming lights.

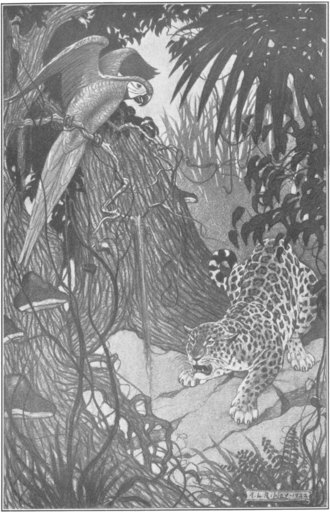

At last he saw that they were the eyes of a jaguar, who was crouching low on the ground and staring up at him intently.

But who could be afraid of anything on a nice day like that? Not Pedrito, at any rate.

“Good day, jaguar!” said he. “Nice Papa! Papa for Pedrito! Your paw, Pedrito!”

The jaguar tried to make his voice as gentle as he could; but it was with a growl that he answered: “GOOD DAY, POLLY-PARROT!”

“Good day, good day, jaguar! Papa, papa, papa for Pedrito! Nice papa!”

You see, it was getting on toward four o’clock in the afternoon; and all this talk about Papa was intended to remind the jaguar that it was tea-time. Pedrito had forgotten that jaguars don’t serve tea, nor Papa, as a rule.

“Nice tea, nice papa! Papa for Pedrito! Won’t you have tea with me today, jaguar?”

The jaguar began to get angry; for he thought all this chatter was intended to make fun of him. Besides, he was very hungry, and had made up his mind to eat this garrulous bird.

“Nice bird! Nice bird!” he growled. “Please come a little closer! I’m deaf and can’t understand what you say.”

The jaguar was not deaf. All he wanted was to get the parrot to come down one more branch, where he could reach him with his paws. But Pedrito was thinking how pleased the children in the family would be to see such a sleek jaguar coming in for tea. He hopped down one more branch and began again: “Nice papa! Papa for Pedrito! Come home with me, jaguar!”

“Just a little closer!” said the jaguar. “I can’t hear!”

And Pedrito edged a little nearer: “Nice papa!”

“Closer still!” growled the jaguar.

And the parrot went down still another branch. But just then the jaguar leaped high in the air—oh, twice, three times his own length, as high as a house perhaps, and barely managed to reach Pedrito with the tips of his claws. He did not succeed in catching the bird but he did tear out every single feather in Pedrito’s tail.

“There!” said the jaguar, “go and get your Papa! Nice papa! Nice papa! Lucky for you I didn’t get my paws on you!”

Terrified and smarting from pain, the parrot took to his wings. He could not fly very well, however; for birds without a tail are much like ships without their rudders: they cannot keep to one direction.

He made the most alarming zigzags this way and that, to the right and to the left, and up and down. All the birds who met him thought surely he had gone crazy; and took good care to keep out of his way.

However, he got home again at last, and the people were having tea in the dining room. But the first thing that Pedrito did was to go and look at himself in the mirror. Poor, poor Pedrito! He was the ugliest, most ridiculous bird on earth! Not a feather to his tail! His coat of down all ruffled and bleeding! Shivering with chills of fright all over! How could any self-respecting bird appear in society in such disarray?

Though he would have given almost anything in the world for his usual bread-and-milk that day, he flew off to a hollow eucalyptus tree he knew about, crawled in through a hole, and nestled down in the dark, still shivering with cold and drooping his head and wings in shame.

In the dining room, meantime, everybody was wondering where the parrot was. “Pedrito! Pedrito!” the children came calling to the door. “Pedrito! Papa, Pedrito. Nice papa! Papa for Pedrito!”

But Pedrito did not say a word. Pedrito did not stir. He just sat there in his hole, sullen, gloomy, and disconsolate. The children looked for him everywhere, but he did not appear. Everybody thought he had gotten lost, perhaps, or that some cat had eaten him; and the little ones began to cry.

So the days went by. And every day, at tea-time, the farmer’s family remembered Pedrito and how he used to come and have tea with them. Poor Pedrito! Pedrito was dead! No one would ever see Pedrito again!

But Pedrito was not dead at all. He was just a proud bird; and would have been ashamed to let anybody see him without his tail. He waited in his hole till everybody went to bed; then he would come out, get something to eat, and return to his hiding place again. Each morning, just after daylight, and before anybody was up, he would go into the kitchen and look at himself in the mirror, getting more and more bad-tempered meanwhile because his feathers grew so slowly.

Until one afternoon, when the family had gathered in the dining room for tea as usual, who should come into the room but Pedrito! He walked in just as though nothing at all had happened, perched for a moment on a chair back, and then climbed up the tablecloth to get his bread-and-milk. The people just laughed and wept for joy, and clapped their hands especially to see what pretty feathers the bird had. “Pedrito! Why Pedrito! Where in the world have you been? What happened to you? And what pretty, pretty feathers!”

You see, they did not know that they were new feathers; and Pedrito, for his part, said not a word. He was not going to tell them anything about it. He just ate one piece of bread-and-milk after another. “Papa, Pedrito! Nice papa! Papa for Pedrito!” Of course, he said a few things like that. But otherwise, not a word.

That was why the farmer was very much surprised the next day when Pedrito flew down out of a tree top and alighted on his shoulder, chattering and chattering as though he had something very exciting on his mind. In two minutes, Pedrito told him all about it—how, in his joy at the nice weather, he had flown down to the Parana; how he had invited the jaguar to tea; and how the jaguar had deceived him and left his tail without a feather.

“Without a feather, a single blessed feather!” the parrot repeated, in rage at such an indignity. And he ended by asking the farmer to go and shoot that jaguar.

It happened that they needed a new mat for the fireplace in the dining room, and the farmer was very glad to hear there was a jaguar in the neighborhood. He went into the house to get his gun, and then set out with Pedrito toward the river. They agreed that when Pedrito saw the jaguar he would begin to scream to attract the beast’s attention. In that way the man could come up close and get a good shot with his gun.

And that is just what happened. Pedrito flew up to a tree top and began to talk as noisily as he could, meanwhile looking in all directions to see if the jaguar were about. Soon he heard some branches crackling under the tree on the ground; and peering down he saw the two green lights fixed upon him.

“Nice day!” he began. “Nice papa! Papa for Pedrito! Your paw, Pedrito!”

The jaguar was very cross to see that this same parrot had come around again and with prettier feathers than before. “You will not get away this time!” he growled to himself, glaring up at Pedrito more fiercely than before.

“Closer! Closer! I’m deaf! I can’t hear what you say!”

And Pedrito, as he had done the other time, came down first one branch and then another, talking all the time at the top of his voice:

“Papa for Pedrito! Nice papa! At the foot of this tree! Your paw, Pedrito! At the foot of this tree!”

The jaguar grew suspicious at these new words, and, rising part way on his hind legs, he growled:

“Who is that you are talking to? Why do you say I am at the foot of this tree!”

“Good day, Pedrito! Papa, papa for Pedrito!” answered the parrot; and he came down one more branch, and still another.

“Closer, closer!” growled the jaguar.

Pedrito could see that the farmer was stealing up very stealthily with his gun. And he was glad of that, for one more branch and he would be almost in the jaguar’s claws.

“Papa, papa for Pedrito! Nice papa! Are you almost ready?” he called.

“Closer, closer,” growled the jaguar, getting ready to spring.

“Your paw, Pedrito! He’s ready to jump! Papa, Pedrito!”

And the jaguar, in fact, leaped into the air. But this time Pedrito was ready for him. He took lightly to his wings and flew up to the tree top far out of reach of the terrible claws. The farmer, meanwhile, had been taking careful aim; and just as the jaguar reached the ground, there was a loud report. Nine balls of lead as large as peas entered the heart of the jaguar, who gave one great roar and fell over dead.

Pedrito was chattering about in great glee; because now he could fly around in the forest without fear of being eaten; and his tail feathers would never be torn out again. The farmer, too, was happy; because a jaguar is very hard to find anyway; and the skin of this one made a very beautiful rug indeed.

When they got back home again, everybody learned why Pedrito had been away so long, and how he had hidden in the hollow tree to grow his feathers back again. And the children were very proud that their pet had trapped the jaguar so cleverly.

Thereafter there was a happy life in the farmer’s home for a long, long time. But the parrot never forgot what the jaguar had tried to do to him. In the afternoon when tea was being served in the dining room, he would go over to the skin lying in front of the fireplace and invite the jaguar to have bread-and-milk with him:

“Papa, nice papa! Papa for Pedrito! Papa for jaguar? Nice papa!”

And when everybody laughed, Pedrito would laugh too.

The End

Works Cited

“Green bird on brown tree branch during daytime” by kanchana Amilani is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Two green birds on brown tree branch” by Sharath G. is licensed under the Pexels License.

“Green parrot on person’s hand” by Ciao is licensed under the Pexels License.

“Green macaw” by Juan Camilo Guarin P is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“White window curtain on window” by Vagelis Lnz is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Window” by Stefan Galescu is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Green and yellow bird flying” by Érik González Guerrero licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Black and white eye illustration” by Angel Luciano is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Green bird” by Egor Kamelev is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Parrot” by Maxx Rush is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Parrot” by Sreenivas is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Green bird on tree branch” by Alonso Romero is licensed under the Unsplash License.

“Leopard fur” by Pixabay is licensed under CC0 1.0.

© 1922 from South American Jungle Tales by Horacio Quiroga. Authorized translation from Spanish (Cuentos de la Seloa) by Arthur Livingston. First published in 1922 by Duffield and Company. This story and all images, gifs, and audio included are in the Public Domain under Creative Commons license.

About the Author

Horacio Quiroga was a Uruguayan short-story writer with a unique imaginative style of writing about the struggles of man and animals to survive in the jungle. After traveling in Europe during his youth, Quiroga spent most of his life in Argentina, living in Buenos Aires and taking frequent trips to San Ignacio in the jungle province of Misiones, which provided the material basis for most of his stories, including “South American Jungle Tales”.

About the Curator

Sofi Sanders is an assistant editor of HIVEMIND Magazine, focusing on the visual design of the website as well as this Translating Culture collection and its accompanying article. She is a Russian-American graduate student completing the Global Media and Cultures Master of Science at Georgia Tech with a concentration in Russian. Sofi is currently focusing on the interrelationships within cross-cultural communication and also investigating the state of the Russian news media, particularly with regard to corruption, censorship, and bias. Her interest in speculative fiction stems from fond childhood memories of Lord of the Rings, as well as her passion for cross-cultural (meaning alien cultures too!) reading and writing.