Surrogacy, Star Trek, and Gestation as Translation

By Eliza Rose

The Star Trek episode “The Child,” which opens the second season of The Next Generation, tells the story of two concurrent and equally arduous labors of translation. The starship Enterprise must transport a deadly cargo of viral pathogens to a research clinic that will develop a vaccine. Due to the virus’ morbidity, the pathogens must be transported inside an airtight containment module. The margin of error is nonexistent. The ship doctor reports: “if the most innocuous specimen on the manifest list gets loose, it will destroy all life on the Enterprise in a matter of hours.” Meanwhile, ship counselor Deanna Troi mysteriously wakes up pregnant after being visited in the night by a “presence” that entered her body. In the thirty-six hours that follow, Troi experiences the full cycle of gestation and motherhood, bringing her pregnancy to term in a record eleven hours, then birthing and raising a rapidly aging child she names Ian.

What do these parallel plots have in common with translation?

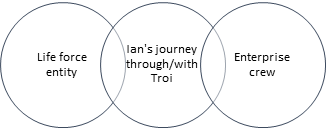

In the pathogen transport, as in Troi’s maternal sprint, a message is transmitted from sender to receiver with much onerous labor in between by intermediary agents. The genetic information contained in the pathogens must be chaperoned on its voyage by experts in multiple fields – engineers, doctors, medical trustees, transporter operators and command officers. This team of “translators” (the word meaning those who carry across) will deliver the lethal “text” in the containment module to be “translated” into a vaccine. Pathogen will be converted to antigen, just as in textual translation, Czech words might be converted to English ones. Troi, likewise, is conscripted into the labor of birth so that two alien intelligences can communicate. For as it turns out, her child wears his human anatomy like a costume. In truth, it is an alien “life force entity” that sees no other means of conversing with the starship crew but to journey through Troi’s womb and spend one day under her care. This is first contact: the alien’s goal is to communicate and understand.

In a manner consistent with Star Trek episode formulas, these parallel plots have symmetries and points of convergence, and the pathogen transport shadows Troi’s gestation as a second translational task. Captain Picard establishes this parallel in a supplemental log: “We are faced with two major problems: Troi’s child and the deadly cargo we are about to take on.”

Insofar as Troi, bodily and emotionally, is a conduit for first contact, and insofar as the life she gestates is and is not her own, her pregnancy resembles the conditions of surrogacy, which has been richly theorized by Sophie Lewis. For Lewis, though commercial surrogacy is currently rampant with worker exploitation, it also carries emancipatory potential:

Let’s bring about the conditions of possibility for open-source, fully collaborative gestation. […] Let’s hold one another hospitably, explode notions of hereditary parentage, and multiply real, loving solidarities. Let us build a care commune based on comradeship, a world sustained by kith and kind more than by kin. Where pregnancy is concerned, let pregnancy be for everyone. (Lewis 2019, 26)

Like a skillful translator, Lewis rewrites exploitative labor conditions into the premises of a revolutionary program. By redrafting the dystopia of an abusive industry as a utopian “care commune” to come, Lewis brings a dialectical ambivalence to the reality of outsourced surrogacy under capitalism. Her recuperative critique of the institution of surrogacy even outshines Fredric Jameson’s provocative adoption of Wal-Mart as utopia. Jameson described his “utopian method” as:

a prodigious effort to change the valences on phenomena […] and experimentally to declare positive things that are clearly negative in our own world, to affirm that dystopia is in reality utopia if examined more closely, to isolate specific features in our empirical present so as to read them as components of a different system. (Jameson 2010, 41)

Rewriting dystopia as utopia by “reading” existing phenomena as “components of a different system” sounds to me like an act of translation. Lewis and Jameson’s utopian “translations” have inspired my efforts to glean lessons from Troi’s radical surrogacy.

By consenting to “hold hospitably” an alien life force, Troi practices the “real, loving solidarity” envisioned by Lewis. Her thirty-six hours of motherhood are a tutorial in the ethics of transformative translation where input does not equal output, but some genuine connection between two ways of being and thinking is nevertheless made.

When android crewmember Lieutenant Commander Data tells pregnant Troi: “Although I understand, in technical terms, how life is formed, there is still a part of the process which eludes me,” he might as well be talking about translation. For is translation not an act of midwifery (of bringing into life) that requires copious technical knowledge of two languages, but for which some hidden part inevitably eludes, lost in translation? A translation’s strength can be gauged intuitively, based on the adapted text’s power to stir emotion in its readers. A similarly intuitive resonance beams from Data’s eyes when he witnesses Troi’s childbirth. Though this experience may not have added to his technical knowledge on the subject, his radiant green eyes suggest that he has finally grasped its essence (one of so many proofs throughout the series that this Tin Man does have a heart).

Data’s otherness as an android among humans equips the show with a permanent translation interface. Data must constantly translate human social etiquette to terms computable to his positronic brain. Chief Medical Officer Katherine Pulaski commits an error of translation when she disregards the preferred pronunciation of his name:

DATA: Day-ta.

PULASKI: What?

DATA: My name – it is pronounced Day-ta.

PULASKI: Oh?

DATA: You called me “Dah-ta.

PULASKI: (Laughing) What’s the difference?

DATA: One is my name. The other is not.

Pulaski’s slip is a case-in-point for the trials of translation, for the source text inevitably exceeds the letters on the page. Data’s right to control his name resonates with the politics of chosen names in trans and nonbinary communities. The anti-android prejudice discernible in Pulaski’s “what’s the difference?” has much in common with the transphobia of those who neglect to affirm chosen names.

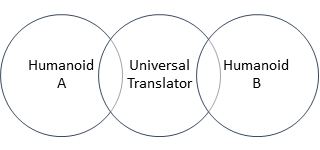

By meditating on onerous translations, “The Child” disrupts a narrative premise fundamental to the Star Trek universe: the clean elimination of language barriers. The conceit of the universal translator – a device so omnipresent, inconspicuous, and effective that it typically goes unmentioned – is what makes possible all humanoid interaction on the show. This device is the nightmare of career translators who caution against the obsoletion of their trade as AI-translation becomes a cost-effective industry norm. Starfleet’s universal translator rarely impedes social and emotional nuances of communication. Surely, it could also tackle Elena Ferrante or Olga Tokarczuk without deadening their prose. There are, of course, exceptions to the tool’s dependability. The device proves clumsy when up against the metaphor-saturated Tamarian language (Kolbe 1991) or the Sheliak’s authoritarian newspeak (Bole 1989). These translation glitches, however, serve as reminders of the convention’s importance for the Star Trek universe. That the universal translator tacitly asserts English as a lingua franca of infinite range has been problematized by scholars of Star Trek’s translations and adaptions in other parts of the world (Caron 2003, Smith 2008).

In “The Child,” the universal translator typically facilitating alien discourse is replaced by young Ian:

In the scenarios above, the middle entity enables conversation. Equipped with handy translators, alien humanoids engage in diplomacy, trade negotiations, or first contact. Ian, meanwhile, samples from human experience, his knowledge of which he will then convey back to life forces of his kind. In this case, the “device” enabling mutual understanding is Ian’s human “tourism” and Troi’s radical hospitality.

Sophie Lewis’ description of pregnancy as “the production of that more than one and less than two” (Lewis 2019, 1) aptly captures Ian’s paradoxical status as genetic duplicate of his mother and as a “life force entity” so alien to humanoids that this 36-hour saga is needed for a simple act of communication. Ian inherits his mother’s genes (half-human, half-Betazoid) along with her dark-pupiled eyes, black curly hair and pearly complexion. That he carries her father’s name, Ian Andrew, confirms his status as an extension of her genetic line. Yet while Ian’s genetic identity is recombined from his mother’s, he is also alien to her. He is sameness and difference together – a fitting metaphor for a good translation, which “duplicates” a source text in a wholly foreign tongue.

Troi’s translational victory is to accept the alien she harbors in her abdomen as her own and to prioritize her empathic bond with it over all rational reasons to distrust and eject her interloper/interlocutor. This comes naturally to Troi, for her Betazoid heritage grants her potent empathy. Her surrogate pregnancy seems to literalize the role of mediator so often imposed on her as the starship’s in-house empath. The scene of childbirth dramatizes the contrast between Troi’s acceptance of the unknown and her male crewmates’ paranoid perception of the embryo as a threat to ship security. A ring of male officers (including Troi’s former and future lovers) flanks the sickbay where Troi gives birth. Their stupefied expressions speak volumes: what they are witnessing lies outside their ken. Whether out of female solidarity or a vocational devotion to the protection of life, Dr. Pulaski unquestioningly accepts Troi’s choice to have the baby. Much is conveyed in Troi’s brief words “thank you, doctor, for everything,” spoken in the afterglow of birth, tears dripping from her nose.

In terms of Troi’s emotional attachment, the child she births is emphatically hers. The alien life force chooses her (skimming past a sleeping male figure before continuing to Troi’s quarters). It has chosen well: Troi does not hesitate to psychologically adopt the anomaly in her uterus: “Captain, do whatever you feel is necessary to protect the ship and the crew, but know this: I’m going to have this baby.” Beyond its powerful affirmation of reproductive rights, this statement initiates an arc of pathos that reaches its apex when the alien departs and Troi must say goodbye. Subdued lighting and a haunting musical score conspire to paint Troi as the picture of maternal love. Marina Sirtis’ arresting performance elevates this portrait from cliché to poignant tragedy.

This episode has drawn criticism for its acceptance of Troi’s “insemination,” which could be interpreted as rape given Troi’s lack of consent when a “presence” “enters her body.” Tellingly, it was men (Handlen 2010, Hunt 2013) who sounded this alarm, and their analyses disempower the very person they purport to protect by wresting away Troi’s control over the story of her alien intercourse. One definition of consent that bears on Troi’s case comes from Kimberly Ferzan, who argues: “the best conception of consent – one that reflects what consent really is – is the conception of willed acquiescence. […] It is the consenter’s act of will, his or her choice that makes the consentee’s actions permissible” (Ferzan 2016, 398, 406). Troi’s “willed acquiescence” to the situation she wakes up to was good enough for Picard and her crewmates – it should be good enough for her audience as well.

Given Troi’s unassailable status as Ian’s mother, are their grounds to describe her pregnancy as an instance of surrogacy? How does surrogacy differ from normative pregnancy, really? This question lies at the heart of Lewis’ book Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family. Lewis’ theorization of surrogacy and gestational work underwrites her radical proposal to abolish the nuclear family. She envisions a future of communal kinships where babies belong to everyone, as do duties for their care, and where babymaking answers to collective needs and desires (Lewis 2019, 168). How does this critique of the capitalist family land in the 24th-century fully automated quasi-communist Federation? No one contests Troi’s exclusive maternal custody of her child. Nevertheless, Ian is automatically welcomed into the Enterprise school, which approximates a welfare institution as an all-access service that socializes care.

Curiously, this episode ends with a crew-wide commitment to share parental duties for another minor onboard. Wesley Crusher, son of a former crewmember, requests to stay on the Enterprise after his mother has left.

PICARD: His remaining will create difficulties for all of us.

RIKER: Yes, indeed. With his mother gone, who will see to his studies?

PICARD: Exactly. Of course, those duties will fall to Commander Data.

RIKER: And who will tuck him in at night?

Chief of Security Worf volunteers for this duty, while First Officer Will Riker consents to help the boy “become a man,” whatever that entails. In their decision to collaboratively raise Wesley, the Enterprise crew lives up to the starship’s utopian promise as a “care commune” where non-Oedipal family structures supplant biological kinship. Monogamy is but one of many ways to organize romantic attachment on a starship, and by no means the dominant one, as Troi’s casual arrangement with Riker attests. Even as his Imzadi(beloved),she holds no exclusive claim on his love, nor does he on hers. Troi’s friendship with Beverly Crusher, solidarity with Dr. Pulaski, and alliance with Lieutenant Ro Laren (her occasional rival for Riker’s affections) are instances of feminist “kinning” (Firestone 2015, 77; Lewis 2019, 147). One “use” of this particular future (as Jameson might put it) is its unstrained modeling of alternative kinship structures.

Troi is not named in the division of labor outlined for Wesley’s care, but as Picard doles out duties, an affectionate smile brightens her face, which was so recently stricken with grief over Ian’s departure. Surely, she too will take part in the rearing of the boy, perhaps replacing her rapid, intense adventure in motherhood with her longer, slower, partial mothering of Wesley.

Will this be enough? Something tells me no. As a human-alien hybrid herself, Troi seems tailored for the task of mothering a non-humanoid. Her empathy will always overpower her distrust of the strange. She furthers the science-fictional trope of aligning feminine subjectivity with alien sentience, as in Stanisław Lem’s Solaris, where a planetary sentience dons the bodied form of Rheya – deceased lover of the novel’s male cosmonaut-hero. While the conflation of female Other with alien Other reeks of male chauvinism, it has been reclaimed in Laboria Cuboniks’ vision of xenofeminism, which cherishes the alien within and rewrites the problem of alienation as an emancipatory path (Cuboniks 2018). I can imagine no truer xenofeminist than Troi seated on the bridge, draped in flowy maternity robes that elegantly hug her alien bump. A tranquil Troi assures her captain: “I should be feeling uncomfortable with all the changes in my body, but I don’t. I feel fine. Better than fine. Wonderful.” Troi’s receptivity to the hitchhiker in her womb marks her as an ideal xenofeminist and translator, for translators must also greet the unknown with open-ended hospitality and patience. Lewis has shown us that gestation (harboring a stranger in the self) is not an exception to human sociality but its basic rule:

…the fabric of the social is something we ultimately weave by taking up where gestation left off, encountering one another as the strangers we always are, adopting one another skin-to-skin, forming loving and abusive attachments, and striving at comradeship. (Lewis 2019, 9)

Troi’s 36-hour discourse with the alien inside and then outside her body leaves both interlocutors transformed. As Ian grows, his presence emits Eichner radiation into the ship’s internal atmosphere, causing a breach in the containment module carrying the lethal pathogens. This incident reminds us that sociality is leaky: when bonds form, membranes rupture. Comradeship, like translation, is a story of imperfect containments.

This much is evident from Troi and her alien’s farewell. Ian’s human body dissolves into light particles, mirroring the shimmer of Troi’s face awash with tears. Troi cups the life force – now a quivering spark – in her palms. What follows is an inward dialogue where two minds meet. The words exchanged are for them alone to know, but in their course, Troi gains what she needs to begin to grieve her loss. By “holding hospitably” alien life, Troi teaches us how to adopt the other under the skin and how to form attachments based on love rather than threat and defense. “The Child” is Troi’s tutorial in comradely translation.

Works Cited:

Caron, Caroline-Isabelle. 2003. “Translating Trek: Rewriting an American Icon in a Francophone Context.” The Journal of American Culture, Vol. 26, No. 3, 329-355.

Cuboniks, Laboria. Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation. New York & London: Verso, 2018.

Ferzan, Kimberly Kessler. 2016. “Consent, Culpability, and the Law of Rape.” Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. Vol. 13, No. 2, 397-439.

Firestone, Shulamith. The Dialectic of Sex. London: Verso, 2015.

Handlen, Zack. “Star Trek: The Next Generation: ‘The Child/’Where Silence Has Lease’/’Elementary, Dear Data.’” A.V. Club, June 3, 2010: https://tv.avclub.com/star-trek-the-next-generation-the-child-where-sile-1798165136 (Accessed 2/15/21).

Hunt, James. “Revisiting Star Trek TNG: The Child.” Den of Geek. April 19, 2013: https://www.denofgeek.com/tv/revisiting-star-trek-tng-the-child/ (Accessed 2/15/21).

Jameson, Fredric. “Utopia as Method, or the Uses of the Future.” Utopia/Dystopia: Conditions of Historical Possibility, ed. Michael D. Gordin, Helen Tilley, Gyan Prakash. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010, 21-44.

Lewis, Sophie. Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism against Family. New York & London: Verso, 2019.

Smith, Iain Robert. 2008. “’Beam Me up, Ömer’: Transnational Media Flow and the Cultural Politics of the Turkish Star Trek Remake.” Velvet Light Trap. Vol. 61, 3-13.

Television episodes:

Bole, Cliff. Star Trek: The Next Generation. Season 3, Episode 2, “The Ensigns of Command.” Aired October 2, 1989, on broadcast syndication.

Bowman, Rob, dir. Star Trek: The Next Generation. Season 2, Episode 1, “The Child.” Aired November 21, 1988, on broadcast syndication.

Kolbe, Winrich, dir. Star Trek: The Next Generation. Season 5, Episode 2, “Darmok.” Aired September 30, 1991.

© 2021 by Eliza Rose.

About the Author

Eliza Rose is Assistant Professor and Laszlo Birinyi Sr. Fellow in Central European Studies in the Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. She received her Ph.D. in Slavic Languages from Columbia University in 2020. She researches visual culture and science fiction from Poland and East Central Europe. Her in-progress book project, Working the Base: Alloys of Art and Industry in the People’s Poland, is a cultural history of art and film in the industrial workplace in late-socialist Poland. She is an author of science fiction and alumna of the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Workshop. Her stories can be found in Interzone and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and have been translated into Polish and French.