by Daniela Tomova

Editor’s note: This is a multimedia story that “translates” the text of the story into a visual and auditory narrative. For the full experience, please watch on a computer, turn audio on, and play the files as you go along. You can check your audio by playing this file before you start the story.

Please scroll down to begin.

Bashi—yes, the one from my work as a guide on Everest—calls me at 4:00 a.m. my time.

“Enna, how soon can you get to Lukla?”

“Whasshappened,” I am immediately awake. “Is someone hurt?”

“No,” he doesn’t even bother to hide the excitement in his voice. “Pack up your oxygen and that prehistoric thing you call a mask. We’re getting Yellow Jacket down the mountain.”

Maybe it’s my state of mind right now, but that’s all the convincing it takes. I cash in all the overtime I’ve accrued—considering how it was earned, it feels less heartbreaking to use it for a good cause—and finally take that vacation you’ve been begging me to take.

It’s been seven years since Khumbu and I last saw each other and we’ve both aged shockingly in that time.

The glacier’s ice has thinned and retreated. The icefall above is eroded—I dread to imagine how dangerous to traverse it is now. You remember the stories, right? Twenty-meter cracks opening up where there weren’t cracks before, ladders with people on their backs collapsing into the depths, ice blocks the size of houses dropping on top of people—almost all of that happens during the icefall trek. That’s the thing about Everest—she warns you upfront what you are walking into.

At the site of the old Basecamp, the tents have taken over for the season. A choppy sea of brightly-colored fabric, ten— hell, twenty times the size of the old Basecamp rears in the chilly wind around me. People, all strangers, tread between the cabins and toilet tents.

I leave my backpack outside the old common cabin, and walk in to melt some snow for coffee. The cabin is dark and empty. That is, until Bashi walks in and fills the whole space with his laughter. A tight bear hug later, he gives me the status. He and four teams—twenty-three people in total, mostly sherpa, have spent the day setting up ladders through the icefall and repairing the fixed rope all the way up to the summit.

The season starts in two weeks.

“Shit. It’s still March.”

“Woman, you’re really out of touch with earth matters,” Bashi laughs darkly, “climbs have been starting in early April for five years now. It gets too unstable as early as May these days.”

“That’s how you got permission to start getting the bodies down?”

“Not just permission. As of this year it’s actually good money. With all the thaws and erosion, the mountain is spitting out bodies all over the trails. Almost from out of the blue. I’ve been working the companies since you left, and finally, finally negotiated them up to five percent of their total income—per expedition—if we clear out the routes before they start.”

“Damn. Even the virtual climbs are paying?”

“They are the ones who don’t care,” he laughs and takes off his hat. There is a bit more salt than pepper in his regal mane these days but he’s otherwise the same Bashi who led my first expedition here, 20 years ago, and then saw something in me worth a place on his team and a position where people trusted me with their lives. “They actually like bodies. Adds some authenticity. But I they aren’t the ones paying my rent or the guides’ kids’ education, so—”

His olive skin is still smooth, I think to myself mildly envious. Everyone on my Space Elevator crew, even the kids—in their 20s or 30s—all of them quickly develop a fine, creeping web of wrinkles but Bashi, who’s been hoping in and out of the active death zone for, what is it now, thirty years, is still ageless.

“So, Yellow Jacket? When do we go get her? I’ll need some brief acclimating but—.”

“Acclimating? Do they keep you that well oxygenated in Space Elevator Maintenance? Isn’t air even more expensive there? How is it there? I’ve been thinking about hanging my oxygen mask here and finally making some proper money. If I make it the next few seasons, that is—”

“Of course we get plenty of air—we keep the cars running and they are what brings in the money.

“By the way, it’s Space Tours Repair and Recovery,” I’ll have him know. “Mostly people recovery. Which is why I got offered the job. Working here was the closest experience you can get to physically handling emergencies in space construction. Our division is half ex-NASA and SpaceX, half oil-rig engineers but whenever something goes wrong it’s not the drones they send—it’s my team. High-alt discipline is what saves lives. It doesn’t always make international news but people go missing in the high-alt stations—passengers, crew. We get most of them back alive. But not all. You know how it is. You can never make it perfectly safe when there’s paying customers involved. There’s still bodies to recover—there always is.”

I don’t have to say what we’re both thinking—that it’s even worse when there’s no body to recover, just a big dark wound somewhere in the ice—like where Bashi’s wife is. Or a hole somewhere in space—

Funny thing was, space was supposed to be the more straightforward job.

But I’m not here on my dime, the philosophizing can wait till I’m back home.

“So, Yellow Jacket,” I say. “When can we get her?”

I know I sound eager as a puppy. I don’t care. I’ve been waiting for this ever since my first climb.

Bashi looks evasive.

“That’s why I called you,” he says. “This one is going to be a little bit unusual.”

He looks away from me.

“We have to go next Thursday, regardless of weather.”

“Why is that?”

He looks around to see if anyone but us is in the cabin. No one is. The customers are in the fancy cabins, the ones with the solar-powered espresso machines and the solar-powered karaoke and the phone chargers.

“She asked for you,” he says.

“Who did?”

“Yellow Jacket.”

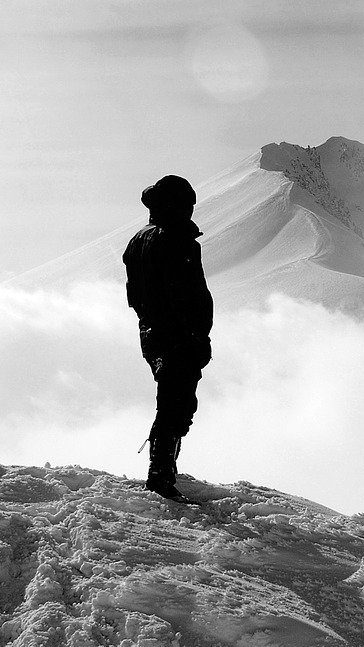

When you climb Everest, the bodies keep you company.

The living don’t have time for you but the bodies do.

The dead are there—all the way up the summit and back—a reminder that you are in their world now, that your own body is actively dying with each struggling breath, each numb step, each swing of the axe: that your only goal is to make it to the summit and down before death catches up. They are the ones who didn’t make it. Not because they were less prepared or less capable or less driven. Just pure shit luck.

Most of dead are anonymous—a hand through the ice, a prone figure facedown around the corner, a a dark shape on a ledge below you. Others have the kind of mythical names you get only in death—Southpaw; Shadow of the Mountain; not one but two Sleeping Beauties, both now identified, recovered and buried by their families—and, as of the late ’90s, Yellow Jacket. Although, before I left the business, we were starting to suspect she had been there for much, much longer.

She sits in an ice crevasse two thirds of the way to the summit from Camp 4, on the South Col trail. Her cave is just off the trail, hidden if you stick to the ropes but, in bad weather, if you get lost on your way down—there is more than a small chance you’ll find her.

Or, if you believe the stories of people who have spent a night on the mountain and survived, she’ll find you.

I don’t know if I fully believe those stories—not even my own—that’s why I left them on the mountain. Outside, I am the empirical type, mostly. Some stories—some experiences—are only alive in places of certain gravity. But when you’re here on the mountain, whether it’s your first time or the last, you can’t escape the realization that the Goddess Mother has her own reality. Her own physics. The sky is thinner above camp 4. The stars are closer. And Yellow Jacket is nearby.

These days, I have other mythologies to reckon with. We have our own kinds of ghosts in space—you know this well. Funny, isn’t it? How every time we humans cross a boundary into a world that is actively rejecting us, it’s as if the ghosts are already there, waiting for us.

My first meeting with Yellow Jacket wasn’t special, though I remember the day itself. You know how sometimes at night my brain is on fire and I can’t sleep. At these times I often pick at the memories of that inaugural Everest climb of mine just so I can physically cringe at my stupidity and my pure dumb luck. If it hadn’t been for Bashi—

It was May 15th, 2023. Eighteen years ago. The sky was that dark-saphire, eight-thousander-blue expedition leaders dream of. I was in Bashi’s group, thoroughly and fanatically prepared. This was it. This was my one chance to summit the great mountain. I had been saving for ten years. Ten years working maintenance in the London Metro—the best-paid job for us Balkan immigrants in the UK at the time—to save enough money for this climb. I was still ten years’ worth of savings away when the foreman’s brother—Bashi, heard about my dream and offered me a place in his expedition at half price.

My backbreaking work hauling reels of wiring and installing cable hanging from wires upside down came with one bonus—I was in a great climbing shape—with the lungs of an ox and the lean muscle of a long-distance runner.

At 12:55, comfortably before the 14:00 cutoff point Bashi had set up for our expedition, I summited. Shockingly easily too. That should have rung the warning bell. Hell, it should have rung a damn fire alarm in my head. Yes, on my way up, in the last hour, the oxygen deprivation had made me stumble dangerously and I’d opened up the valve of my oxygen tank—a little bit, I had thought. But I was still in full control of my body and my senses.

I was comfortably on the way down when my heart started loping uncontrollably. I struggled for breath. Head started pounding, painfully, with every breath. My vision darkened. My steps got slower, clumsier. I couldn’t judge how far down the ground was and each step either undershot or overshot it. I tripped and dropped the fixed rope and suddenly couldn’t find it anymore.

Bashi, who was helping a client up to the summit apparently saw me walking, as he later put it “like a toddler learning to walk, no offense, it’s what happens. You survived and now you know.” He fought me for my oxygen bottle—I didn’t want to let go—and gave me his spare one and then sat me down by the route to rest until he came back.

So I sat.

So I thought I sat.

After a certain point, I remember separate moments but not how they related to each other.

I was crouching on the ground, trying, but failing, to calm my breath over my panicking heart and burning lungs

I drank a little water.

People slogged by, too exhausted to even notice me. Some even tripped over me—I think.

I took off my iced-over goggles to wipe them. Possibly drank some more water—I remember at least thinking I had to. I put the goggles back on, and when I looked up, a person was seated on a block of ice in front of me. Their face was hidden deep in the hood of their coat. It was daylight and despite my tunneling vision, I was able to see clearly how bright the coat was. In my state I couldn’t tell exactly, but something was very strange about it.

“We need to help this person too.”

Under the snow and ice, its color was an uncommon yellow—or maybe a faded orange. Its shape was oddly industrial. I couldn’t determine the make or age. None of the climbers on that day were wearing a parka that color. Was this someone from a later expedition? How much later? How long had I been here? Days? Was I dying? Still sitting, I stared, blinking, trying to make out the face for what felt like few minutes but must have been much longer because a finger snap in front of my eyes made me look up and there was Bashi, framed by the orange twilight, angry at me for making him search for hours, long after we should have been back to Camp 4.

I stood up.

“We can’t help her,” Bashi said. “Let’s go.”

But I stood up and walked—god, every step was like slogging through cement slurry—those one, two, three steps to the climber. Wish you could—wait, you probably know how it felt.

Do you remember the third nychthemeron of our search for Rada? When we were so wiped out and you used too much graphite on the threading of your oxygen supply and it suddenly loosened?

Do you remember those frantic those 10 meters back to the station, suffocating and struggling to move your feet against the nothing of space? The feeling that your lungs will explode the next second? This is what altitude sickness is like.

So why did I, inexperienced, acutely aware that my body was actively dying, take those three steps?

On Everest, even surrounded by other climbers, for all practical purposes, including the most practical one—survival—you’re mostly on your own. The “no one has the energy to even notice you” kind of “on your own”. The traffic jam paradoxically makes it even worse. Those you can count on can be hours away. Stories of climbers walking by dying people on their way to the summit were branded in my brain and even in the disorientation of altitude sickness, I wasn’t the type to walk away. Even then, I was the type who got people down.

I leaned over the woman. All I could see under the hood were her peculiar giant snow goggles.

“Get up. We’ll share the oxygen bottle. We’ll get you down and get help.”

She didn’t react. I grabbed her shoulder. It was like gripping a stone. A heavy, gloved hand landed on my own shoulder and I turned.

“It’s been very long since anyone could help her,” Bashi said. “This is Yellow Jacket. We have to go.”

That was then. And now, few more encounters with Yellow Jacket and eighteen years later, I know better than to take Bashi’s words at face value. So I wait for him to elaborate.

He takes a long time to get set up. He’s always had this almost ritualistic way of preparing for activities. Watching him prepare anything is almost like a meditation. He starts by walking to the old scarred bench by the long table, pace deliberate and controlled as a heartbeat. I know better than to rush him. It’ll have no effect.

We can hear conversations outside but no one enters. The cabin is dim. Bashi takes off his parka and a couple of intermediate layers of wool and sits down on the bench. I sit next to him. He unlocks his phone, sets it on the table before us, and scrolls through the videos.

I look at him, confused.

“Just watch,” he says and presses the “play” button.

The video starts with a woman talking over a radio in a group tent—in Base Camp, I assume. I don’t know her but she appears to be a Base Camp manager—the people responsible for communication and coordination of the expedition teams. Imagine them as our situation-room coordinators.

“Can you repeat,” the woman says into the radio.

White noise from the radio.

“Jonathan, are you there? Are you awake?” (Here, from experience, it’s becoming clear to me that Jonathan is lost on the mountain and the Camp manager is trying to keep him responsive to give the rescue team a better chance of finding him alive.)

White noise over the radio.

The woman looks anxiously at the person who is filming and turns back to the radio.

“Jonathan, can you hear me? Are you there?”

The radio crackles.

“I am—.”

“Jonathan, stay with us. Talk to me.”

“I’m— awake, Alice” Jonathan replies faintly. “—very tired.”

The woman looks at the forecast on her laptop and then at her watch.

“Jonathan? Listen, the storm will be letting out soon after midnight. That’s an hour from now. We’ll be sending everyone who is in good shape out to look for you at 01:00. Do you read?”

White noise from the radio.

“Jonathan.”

“Jonathan.”

The radio crackles and Jonathan’s voice comes faintly.

“Alice? I see —of them coming. Looks li— Bashi— here”

The woman looks at the person filming. She is confused.

“Bashi is with me, Jonathan. We can’t send anyone out before 2 AM.”

She turns back to the person filming.

“Is there anyone else left on the mountain,” she asks. The image shakes faintly.

“No,” Bashi’s voice replies. “All other expeditions are fully accounted for.”

Alice turns back to the radio.

“Jonathan, talk to me. Just a few hours.”

“—not Bashi. — woman.”

The phone is stabilized on a wooden surface and Bashi enters the frame, sprinting to the radio.

“Jonathan, Bashi here. Did you say a woman?”

He turns to Alice.

“Keep him talking.”

“—Walking towards me. Can’t—her face—ight coat, can’t make—. Bishi, she —next to me. —God—”

White noise.

And then, clearly over the radio, a different voice, a voice like pebbles racing downhill, a voice that you can believe comes from a frozen mouth and cold tongue

“—help me—March 23rd, twen—down the mountain.”

White noise.

And then the voice again, sending icewater down my back.

“—you promised, Enna—”

Bashi shuts off the phone.

“There was more,” I say distractedly, scrolling through a reel of explanations possible and impossible in my brain. Also, this unsettling familiarity in the second voice—what exactly was it I recognized? Not the voice itself but what she said? How she said it?

“That’s it, pretty much. The rest is just white noise and trying to get Jonathan back on the radio” he says and slips the phone in his pocket. “We got him back though. Lhakpa—you met her just before you left the team, right—found him at 5:00 in the morning. Lost two fingertips and two toes but last I heard, he’ll be back.”

“If they can walk, they will be back,” I finish his saying for him.

He looks at me—case in point—and shrugs.

“Well, of course I’m back. You promised me Yellow Jacket. Plus, what is space compared to the Great Mountain,” I say. “And there was no one with him? Jonathan, I mean. When Lhakpa found him?”

Bashi shakes his head.

“And you’re sure Yellow Jacket—You’re sure that’s her”

“No,” he says. “All I know for sure is that her body is frozen solid to the ice. I don’t know what to think about all these stories, including—no offense—yours. But, to be honest, I sold the last companies on body cleanup thanks to this video. For one reason or another. The ghosts of Everest might be exciting for the clients but they make the expedition leaders’ jobs so much more difficult. We have jackasses veering off the trail on purpose on their way down now, if you can imagine. Last year some “Ghost Hunter” reality show team snuck in, fake identities and all, and those jackasses weren’t even trying to summit. Three of them died, which is bad enough but two of their sherpa guides died too trying to get them down. Vile!”

“I heard about it. Couldn’t watch the episode myself,” I say. “Too infuriating!”

“So,” Bashi continues. “All physical expeditions pitched in. That’s decent salaries for more than 20 people for the season. And, look, I’m not even sure the “Enna” is meant to be you. Maybe it’s that effect, what was it called? When people see faces on inanimate objects—“

“Pareidolia,” I say reflexively. “We train our people to be critical of it.”

“Exactly. It wasn’t that clear what the voice said. It could have been antenna, or Elena or even edema. But you are the one I trust up there,” he continues. “Therefore, we say it’s Enna and proceed from here. So what’s in it for you? You get your wish. And your fee. I say we go up March 23rd. If the weather is good, we get her. If it’s bad, we stick close to camp 4 and—one Balkan zevzek to another—we make up a real good story why we didn’t get her and try again with more favorable conditions. But, Enna, it’s your decision here as much as mine. You need to be there with me.”

I look at him, grinning.

“I guess we’re getting Yellow Jacket March 23rd then.”

We get to Camp 4 on the South Col on March 21st. Now firmly in the death zone, we have 48 hours to get the body down. One trip up to assess the location and start freeing her, which will be the hardest part of the job, as she is still frozen solid to the ice block. That’s the biggest unknown. So far, none of the bodies recovered have been completely frozen into the ice. The second trip will be to bring her down to the South Col.

My week of acclimation passed without any major disturbances—just a couple of pounding migraines, which for me amounts to a bad week in Quito, but a better than expected one on Khumbu—and I am both a bit tired and a whole lotta excited to see the familiar burnt orange of the C4 tents. This feeling never gets old. It never becomes routine. And even though I am not summiting next morning, a strange sense of anticipation rolls over in my stomach. It’s the expectation of a win, finally a win—something I’ve needed sorely since Rada’s disappearance. In my rational mind I know that Yellow Jacket didn’t hear that promise to help her down but, to be honest with you, Julian, I’m happy I get to keep it nevertheless. I never expected to. And in some small fold of my mind this gives me hope that it’s never too late to keep a promise—

The season doesn’t start until next week but the mostly-sherpa teams have already set up a large stock of oxygen bottles and about two dozen tents. Behind them is a field of bright-orange bodybags, weighted down with stones. The retrieval teams have been busy.

The sun has set and the wind picks up, loud as a jet engine. The sky is clear—it’s been this way for two days, which bodes well for our little mission—and I stay out a while looking for my stars, the ones that keep me company on the long nights in space. The tents and bodybags rustle in the wind like leaves trying to tell me an urgent secret in a language I almost understand.

In a routine unbroken over twelve years of summiting Everest, my brain lights up all night, plucking out and replaying the greatest hits of all fuckups I have made throughout my life. “No one but the dead sleeps well in the tents in Camp 4,” Bashi had told me on my first ascent. I’ve never been able to prove him wrong.

I manage a shallow sleep for maybe two hours and in the fog of waking up, I remember whose accent the voice in the video reminds me of.

No.

Can’t be.

The huge goggles—the bright parka—was it a parka or something I didn’t identify then but will immediately recognize today?

No. That’s a stupid, stupid—

“Enna,” Bashi calls for me outside the tent. “We leave at 11:00.”

—stupid thought.

Can’t be her.

Bashi and I climb up in darkness and silence.

While I still have the energy to think, I try to remember details about Yellow Jacket.

Our second meeting was right after I was hired into Bashi’s team. Lobsang Sherab Sherpa and I were escorting a paying client to the summit. The client, Bob—not his real name—had summited at first try every eight-thousander except for Everest and K2. That was according to his CV. What the CV failed to mention was that he had been all but carried by porters to all those summits. The man went through oxygen bottles the way I go through humitas and we ran out about two hours into our descent. Lobsang told me to keep the client moving and went for more oxygen and, if feasible, more help. I did my best, sometimes physically dragging Bob along where it was safe to, but we were quickly outpaced, first by everyone on who had summited and, finally, by the setting sun.

To Bob’s credit, he didn’t complain or catastrophize. He was actually way sanguine for someone facing the prospect of spending a -25F night exposed on the slopes of Mount Everest with no supplementary oxygen.

“I know you’ll figure something out,” he said more than once. “You seem very capable. We’ll make it.”

At that time, at half his age, I thought that was a praise, maybe an encouragement.

I didn’t realize until a year later, on one of those sleepless nights of chewing gristly memories, that it was neither. That all his life he had been insulated from every consequence by an army of capable, tireless people and that had become his reality. That he actually completely believed he could do anything and overcome anything. That he was the most dangerous kind of client.

But at that time, roped to a my first life-or-death responsibility, believing I can do anything, I slogged down from the Balcony when I noticed that the oxygen deprivation began to affect his behavior. He began stumbling behind me, increasingly confused. I felt him pulling at the rope trying to wander off. I leaned hard forward but he was much heavier than me. Eventually, he managed to drag me few hundred meters off-course to a point where, in the dark, we would be completely lost. I took my knife out and cut the rope. The only real choice now was to let him wander off, most likely killing him or stay with him, risking both our lives. I turned up towards the pale outline of the mountain against the sky and screamed for Lobsang hoping he could hear me.

A faint silhouette, pale grey in the starlight, slowly resolved itself against the snow, approaching us us from the west. Probably Lobsang, who overshot and was now coming back to meet us! I screamed again. Then, as I was watching it, the figure stopped. Now that it wasn’t moving I couldn’t make it out anymore. I was screaming myself hoarse and Bob, uncomprehending and scared, started pulling away. I grabbed the end of the rope I had just cut and held onto it, as if I was holding back an aggressive dog. Few minutes later, Lobsang half-ran, half-slid down the slope to us from the east.

His face, when I could see it, was completely terrified.

“Yellow Jacket, Enna, what did she tell you?”

“What do you mean,” I asked him.

“When she was here, right next to you. She moved her hand up to you and then to the summit, didn’t you see her?”

He pointed to a place where the snow was packed as if someone had been walking on it but it could as well have been me or Bob who had done that.

Bob made it home safely that summer. Another eight-thousander at first try on his CV.

Right until I left the team Lobsang never changed his account of what he’d seen.

The last time I think I saw Yellow Jacket, I was being lifted up through three meters of snow from an avalanche which had hit suddenly and mercilessly.

I was on my way up from the Icefall carrying a couple of replacement radios and oxygen bottles for a team stranded below the Hillary Step when, without warning, the gray skies broke and poured down on top of me. I was instantaneously buried. After a precious minute lost to disorientation, I found where up was and started scraping at the packed snow, fistful by fistful. I’d lost one glove in the fall and was switching the other between hands as I worked desperately.

Something in the snow grabbed my ungloved hand and gripped tightly. A bare hand, cold and hard.

“Hold on,” I tried to yell and dug and dug and dug until the light broke through and I heard loud voices.

Someone gripped my gloved hand and pulled, then two hands scooped my shoulders up. I was still holding onto the hand in the snow but felt it loosening its grip.

“Hold on,” I screamed. “Hey, there is someone else here. Help me!”

The rescuers pulled me up more roughly and just as they lifted my torso out, I looked down inside the hole I had left. In there, an arm in a yellow-colored sleeve was slowly pulling away, snaking back into the packed snow. Instinctively—not my proudest moment—I screamed and kicked my feet up as if trying to swim to the surface.

Once out, I looked back inside the hole. I was crying for some reason. My vision was blurry but I can swear I saw that face and those big goggles—wait, the goggles—Julian, I wonder if my mind is losing the sequence of events again.

The fog appears just before sunrise. When the morning light reaches us, Bashi stops and, just like all those years ago, points to the Brocken Specter ahead of us. I nod, less in childish awe of the phenomenon than usual. Our giant shadows walk off into the horizon ahead of us, their heads brushing the skies, and dissipate with the fog.

“Bashi,” I say, when we take our last break before we reach our target. “Do you remember exactly what Yellow Jacket’s parka and snow suit look like?”

“What do you mean?”

“Does it—Do you know if it looks anything like a space suit?”

“I don’t know what a space suit looks like. Can you describe it?”

“No, forget I said anything. Just having some weird thoughts.”

“Are you feeling okay,” he asks.

“I’m good. Fit and lucid.”

We set off again. I am in front of Bashi now, setting the pace maybe a little faster than reasonable. We reach the crevasse shortly after 11:30.

Yellow Jacket waits for us there.

She is sitting, exactly like the first time I saw her, on the block of ice. With the years, the snow covering her has compacted, melted away and refrozen and melted again, so her clothes are covered in a thick layer of solid ice and frost. I move close to her and pour some defrosting liquid right over her left breast, where I can see the dark outline of what could be a badge. The frozen layer is too solid but the liquid smooths out the surface and briefly turns parts of the ice into a lens. The dark square is a badge. The name isn’t visible—but in the upper right-hand corner is the stylized logo of the Space Tours Company

“What,” I try to say but it comes out as “No!”

“Do you know who she is,” Bashi asks, watching my face.

“I know her.”

Then I try say a name but it won’t come out.

The last time I said her name out loud was when I met her parents to give them the facts. They weren’t satisfied with the official report the way her husband was. They spoke no English or Spanish so I stumbled with whatever I could remember from their language.

Rada, 29 and a senior coworker, M, 37, who had two decades of relevant experience, were assigned to a repair mission to Space Elevator Station 4601 (a small resting area hosting a vending machine bar, a well-curated museum dedicated to dinosaur remains in space, and a gifts hop). The doors of a luxury Go-Gondola-type car carrying five tourists (a family) had malfunctioned and the clients were locked inside. Upon assessment of the situation, Rada exited the station from the maintenance hatch into space, wearing her regulation suit (quality controlled before every mission) and approached the outside panorama windows of the car at 12:47 local time. At 12:52 local time, M saw the family bang on the windows of the door and exited the station through the maintenance hatch, into space, wearing his regulation suit. He radioed calling all standby teams to the station after 20 minutes of searching. After a complete 24-hour search and drone scan, Rada was not located. Subsequent searches were also unproductive. Each member of the tourist family, separately when questioned later, reported that she had appeared to slip on something and disappeared into the emptiness of space.

Her parents wanted more than information. They wanted me to explain the inexplicable. How could someone just disappear in space? Why her?

Why was I here when she was gone?

I tried to answer their questions, perfectly aware I was making them more frustrated.

I don’t have time for shock or for questioning my lucidity. Nothing makes sense right now but the physical action and reaction of our work, so I focus on that. Bashi and I get to work, gently, reverentially, deliberately. He pours a bit of some stronger—and knowing him, homebrewed or at least home-mixed—defrosting liquid and I, eyes steaming with the smell, chisel away at the ice that keeps us from taking Yellow Jacket with us. The sun rises above us and Bashi checks his watch. We have a hard deadline of 15:00 to head back. It’s 14:00 now and we have no more defrosting liquid.

I grab Yellow Jacket’s leg with both hands just above the knee and try to wiggle it softly but there’s no give. We pick up our ice axes and start chiseling again—I on the left side, Bashi on the right. Soon Bashi stops and straightens his back.

“Enna, it’s 3 o’clock. We have to go,” Bashi says. “We’ll be back tomorrow.”

“Just give me half an hour more. See? I’m halfway through,” I say and immediately realize my mistake.

He looks more hurt than disappointed. In all the years I’ve known him, he’s never broken the deadline. I know his reasons, professional and personal but I hoped he would bend the rule just this once. Equally frustrated and embarrassed, I pack in my axe.

Just as we leave, three things happen simultaneously: a small fluffy cloud appears down in the valley, the wind suddenly turns and the realization of what I’ve seen today hits me as the shock wears out.

I haven’t talked to you about this but it was language that started it all. Rada’s working English was understandable but hesitant and I quickly noticed how wide she smiled when I greeted her in what, to me, was the borderlands dialect I learned from my mother but to her was the language of her homeland. Out chats quickly turned into lunches where we spoke what we termed our “mutt language”.

We stayed away from politics, just in case. We spoke about food—curiously, one of the subjects where our languages resembled each other even closer. I brought her jars of homeland—herbs, jams, my secret 12-herb pine syrup, and even the greatest culinary accomplishment no one but me would drink here— homebrewed boza.

I learned that her husband, a Westerner, 15 years her elder, would mock the Balkan food she cooked, so I started making it more often, bringing some extra for lunch. And when a spot opened in my team she put in a request to transfer.

You did warn me against having friends as employees then. Remember?

“We’re not friends,” I told you. We weren’t. We were each a recognition of the other, a confirmation of each other’s full existence. For each of us, that was a need more fundamental than the need for either love or friendship. Of course, that probably made it an even worse idea. I see that now.

We arrive outside Camp 4, the storm at our heels. Just as we are about to get into our tents, Bashi hesitates and turns to me. He says he needs to show me something after I warm up.

An hour later, we meet outside his tent. The storm rages. We lean against the waves of icy snow lashing at us as we walk into the field of bodies. Bashi stops over one of the body bags, wipes the snow blanket on top of it with his gloved hands, unzips it halfway, and looks inside. He motions to me. I approach.

“Look,” he yells.

And I do. My mind is empty. I’m exhausted. I don’t bother to even guess what I am looking for but I see it immediately anyway.

The person inside the bag is wearing an industrial-looking suit the same bleached orange as Yellow Jacket. He, too, has a badge bearing the stylized logo of the Space Tours Company. This logo is different though. One I haven’t seen before.

The identification section of the badge claims that it belongs to William M. Roscoe, employee at the Space Repairs and Retrieval Co. It’s valid from 01.01.2075 to 31.01.2075. His birthday is also listed. Mr. Roscoe appears not to have been born yet.

“This isn’t the only one,” Bashi says.

He unzips three more bags at random. All three bodies are wearing regulation spacesuits at different stages of dissolution. Two of them are different color and probably different departments. The badges, which appear porcelain but are in fact made out of ceramic nanoparticle, are as new although the cheap-ass paint on them has worn out with—I can’t imagine how much—time.

“We started finding them when the trails shifted,” Bashi says. “The regular, climber bodies, if found, are usually found along the trails but the Yellow Jackets are clustered around Yellow Jacket, your Yellow Jacket’s crevasse.”

I stare at them, not understanding.

Bashi mutters something which I can’t hear over the storm’s roar.

“You could have told me all that at Base Camp,” I say.

“How do you think you would have reacted,” he says.

I honestly don’t know.

“Regardless, you should have told me.”

I sleep like the dead for five hours this evening. When I wake up the storm is over but the skies are still overcast. I put on my gear and go to Bashi’s tent.

“We leave in half an hour,” I tell him. “Let’s go get Yellow Jacket.”

Neither of us talks as we climb.

Today is significantly more difficult. We are both wheezing and hacking with every step. I notice I’m using more oxygen than yesterday and suspect so is Bashi. The wind is more vicious too.

We get to Yellow Jacket’s crevasse and wordlessly continue our work. The wind whips the snow around us. The temperature drops and Bashi’s liquid quickly loses its effect.

Today’s turnaround deadline is 14:00. Around 13:30 Bashi looks at his watch and picks up speed as much as he can which isn’t much. I shake Yellow Jacket’s leg and it moves under my palms. I am already working at the edge of my strength. My vision narrows and I open the oxygen valve a little and continue working. Soon events start to lose their continuity again.

It’s 14:00. I am still chiseling at the ice. I know I have to leave but I can’t physically stop my hands. Where is Bashi?

It’s 13:50. Bashi stops for a while and almost hacks his lungs out, doubling over.

It’s 12:20. We are packing up and leaving. Suddenly Bashi isn’t around.

It’s 10:59. I am stabbing at the ice desperately. 45 more seconds to go. Stab. Stab. Stab. 30 seconds. Bashi screws his oxygen valve. I can’t tell if it’s up or down. He walks to me and screws mine up. Clarity floods my lungs and soon my brain too. I look at my watch. It’s 14:20.

“Bashi, it’s 14:20. We have to go.”

“Not. Yet,” he says, coughing with every hit of the axe.

I fight him for the axe.

“We’ll be back,” I say. “I’ll stay on the mountain until we get her. I promise. No need to die now.”

He turns to Yellow Jacket.

“Just get up, you frozen asshole,” he yells in her face and shakes her torso. The ice under her legs cracks a little. “I know you walk around when you want to. Here is the person you wanted. Get up and come down with us.”

He turns and starts packing his axe.

On our way out, dark clouds start crowding the sky. The wind carries the first snowflakes of the coming storm to us. Just before we turn north and away from the crevasse, I turn around. Yellow Jacket is standing by the ice block.

I tap Bashi on the shoulder and point to the crevasse. I don’t even know what I expect him to do. I just don’t trust any of my senses right now. He turns around and his face changes. He looks at me. I’m too exhausted to do anything but shrug.

It’s 14:35 and we’re going back for Yellow Jacket.

It’s 15:57. As with everything else, carrying bodies down the mountain is a lot more difficult than the sherpa make it seem. Every step seems like it’s my last. My dry cough quickly turns into a feeling of drowning unless stop every two steps to cough out the fluid in my lungs. Bashi isn’t faring much better. We are very close to running out of oxygen. I don’t think I’ll have enough for the three hours which we’ll take to get down.

When we got to her, Yellow Jacket was still standing by what we had thought was an ice block. I didn’t have time or energy to look but I think inside that was a regulation maintenance space suit helmet. Though she was now standing, her body was still hard and cold as a rock. And just as immobile. So we laid her down and zipped her into the orange body bag we’re carrying down the trail now.

The three of us made it into camp IV at 18:17. I was right about running out of oxygen but Bashi, once again, saved my ass. Half the time I had thought he was turning his oxygen valve up, he was controlling it to make sure there was enough left for both of us. He was in a bad state when we get here but he is now on AMS medicine and stable. A team is ready get him down to Camp III when the storm lets out. I’ll follow them shortly. I just need to talk to my friend.

The storm is still howling over the field of Everest bodies. I unzip Yellow Jacket’s bag and crouch on the ground next to it with my prehistoric mask and a fresh bottle of oxygen. My fingers rub over the badge, gently so I don’t damage that cheap-ass paint. Under them, letter by letter—R-a-d-a-then space—the name is revealed. I say it out loud. That’s when she finally speaks to me.

Her voice is different. I tell her that.

Voices change when you spend hundreds of years on the mountain, she says.

How is that possible, I ask, when we last talked two years ago.

She doesn’t know. She doesn’t remember much before the mountain. Only flashes of her parents, her home…home food…my name on jars of rose jam. She doesn’t remember the Space Elevator, only space…the hole which spat her up here…my promise to get her home.

My promise, which she repeated as she sat by the hole’s exit, as she walked around at night. My promise which every lost person on the space elevator years from now heard. Home.

Some of the bags about us get restless. A choir of voices rises from the field.

Home. Home. You promised.

I don’t ask them why they can’t go home themselves because I know. As I told you, Julian, the great mountain has her own gravity.

How many people, I ask instead.

Many, many, they say. And many are still in the hole. The hole that is a world of its own. And it’s already filled with our ghosts. Nothing like it on Earth or in space.

So many ghosts.

I’m taking you home, I tell her.

Julian, I’m sending this letter via Bashi. I hope you understand why I have to get back to Everest after I take Rada’s body to her parents. Bashi will show you his video and pictures of the space suits. The bodies will be stored in Kathmandu for as long as my savings hold out. Please, try to convince anyone you can in the company to investigate. And to stop or at least restrict operations until they locate and research the hole. You’re better placed in the company. People who won’t listen to me might listen to you.

I might come back to Ecuador but I probably won’t. Even if I manage to get every one of the bodies down, there is still… whatever it is by Yellow Jacket’s crevasse that is spitting out ghosts.

If you ever want to find me, come to Basecamp and ask for me.

Works Cited

“Banitsa” by Dock is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

“Charlie on Mt. Everest summit” by Didrik J is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Everest Base Camp images by Mark Horrell are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“istanbul, turkey” by balavenise is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Temple Cave Desert Storm by szegvari is licensed under CC0 1.0

2600hzfeedback.ogg is public domain.

All other images are by Pixabay and licensed under CC0 1.0

© 2021 by Daniela Tomova

About Daniela Tomova

Daniela Tomova draws her inspiration from Balkan folklore, the worlds of Ray Bradbury, surrealist Russian science-fiction, and the everyday magic of people who live in the ruins of countless civilizations. She is a graduate of Clarion Writers’ Workshop. Her work has been published in Apex Magazine and 7x7la. Data scientist by day, she lives in an abandoned airport in Oslo, Norway with her partner and their cat.