by Sofi Sanders

From Godzilla and Mothra to Rodan and Gamera, many of Japanese science fiction’s most recognizable characters belong to the kaijū or monster, film genre. Godzilla (1954), the inimitable grandfather of the kaijū genre, is still recognized worldwide both as a pioneer of Japanese mass entertainment and ambassador for Japan itself (Tsutsui and Ito 2006). But what exactly are kaijū? And how did the ancient Japanese concept of powerful animal-spirits transform into the kaijū genre of today?

To begin, kaijū is a Japanese word meaning “monster,” which is a combination of “kai,” meaning mysterious or unknown, and “jū,” meaning beast. This gives the term a negative connotation, reminding one of powerful and unsettling mysteries which threaten the human world. However, this connotation of mystery also relates closely to the spirit world prevalent in Japanese folklore as well as to the worship of spirit-gods in Shintoism. While the kaijū film genre is relatively young, its origin can be traced back to ancient Japanese legends and religious beliefs. Some of the earliest Shinto texts and Japanese legends featured such creatures, such as the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), which dates back to the 8th century.

Before diving into the historical context of Japan, it is vital to first review some of the most important Japanese terms for the ancient supernatural creatures that inspired the kaijū genre. Parsing the meanings of terms such as kami, yōkai, yūrei, and onryō is no simple task, as many Japanese folklorists and scholars have discovered. To be fair, it is already difficult enough to settle on one absolute definition for any such creature in English. Try to define the word “monster” or “superhero,” then ask yourself if these definitions are truly all-encompassing. For example, in defining a monster, you might think of the legendary Kraken, or the Uruk-hai from The Lord of the Rings franchise, but what about Appa, the furry sky bison from Avatar: The Last Airbender? All of these creatures have enhanced supernatural abilities and are “unnatural” when compared to the human world. But are they all monsters? And if not, where does one draw the line?

Clearly, there are some universal difficulties in neatly defining categories of supernatural creatures, but there are also some additional complications when defining creatures in Japanese folklore. This is not only because many kanji (Japanese characters) originate from Chinese and now hold different meanings, but also due to the complex spiritual and religious histories of many Japanese supernatural concepts. Most notably, Shinto, the native religion of Japan — and one of its most culturally influential as a result of being practiced for thousands of years — revolves around the veneration of kami. Kami are spirits or spirit-gods who have supernatural abilities. They reside in a variety of natural objects ranging from the sun to rocks to the souls of the dead. These kami are believed to exist in a hidden realm, and their presence and actions are said to have influence over people’s lives. In line with the Taoist idea of yin and yang, which attributes two “faces” to one entity, kami are said to have both positive (nigi-mitama) and negative (ara-mitama) aspects. By paying respect to the positive while avoiding the negative, one can encourage the kami to work in one’s favor whilst avoiding misfortune.

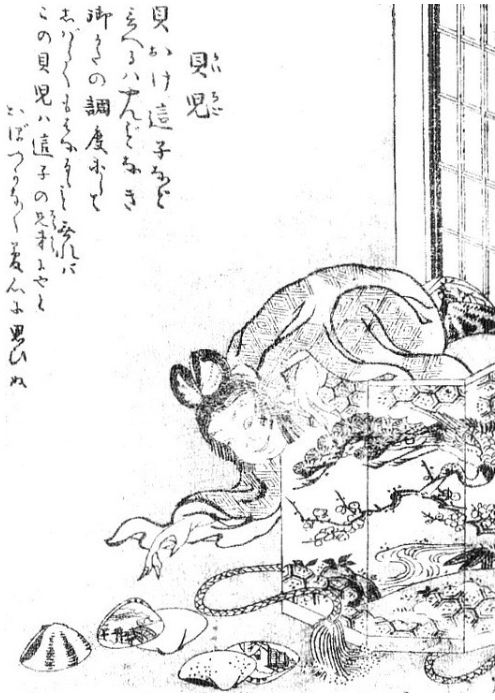

Due to the immense power of these kami, worshipping them is seen as necessary in order to avoid retribution. In fact, un-worshipped kami can turn into yōkai, which is loosely translated as monsters or “bewitching mysteries.” Yōkai are often connected to uncanny, strange, and supernatural phenomena. Yūrei, or spirits of humans still wandering the Earth, are defined as either a subset of yōkai or are distinguished from yōkai by the fact that yūrei are bound to a specific person whereas yōkai are bound to a specific location. Onryō, popularized by The Ring (2002), are “vengeful spirits,” or yūrei driven by vengeance. As opposed to other more animal-like yōkai, onryō are described as more ghost-like and have incredible supernatural powers that allow them to create natural disasters such as earthquakes and storms.

Furthermore, the meanings of many Japanese supernatural terms have changed over time. As new manga and other content starkly reimagines traditional supernatural creatures, they may become unrecognizable when compared to their ancient origins (Tsutsui and Ito 2006). While few would argue that the kaijū film stars of today could be called yōkai or yūrei, the kaijū story type depicts kaijū as kami in that they are often manifestations or representations of nature which must be respected, lest they unleash devastation upon humans. Clearly, the kaijū genre is rooted in Shintoism, Buddhism, and Taoist philosophy, wherein the mega-monsters of the screen represent Japanese spiritual belief in the sheer power of nature, as well as the foolishness of man in trying to overcome the natural world.

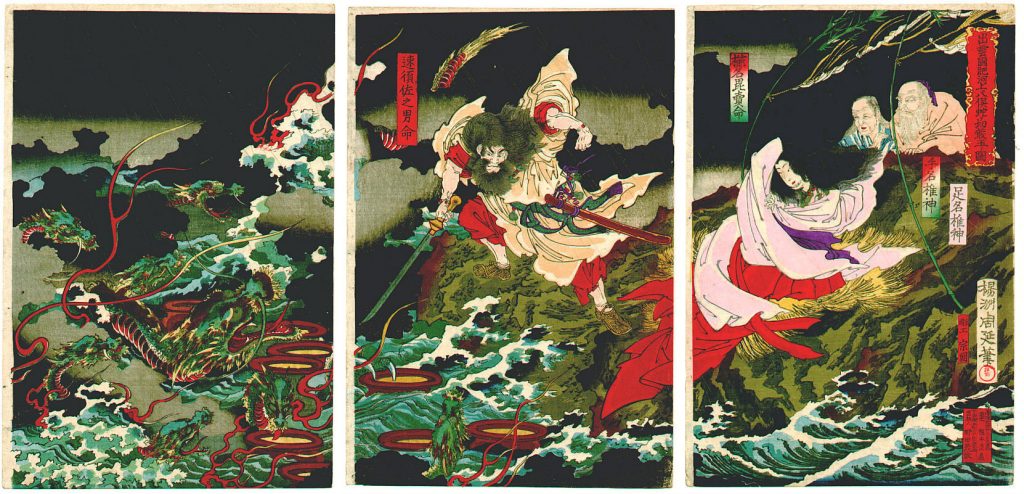

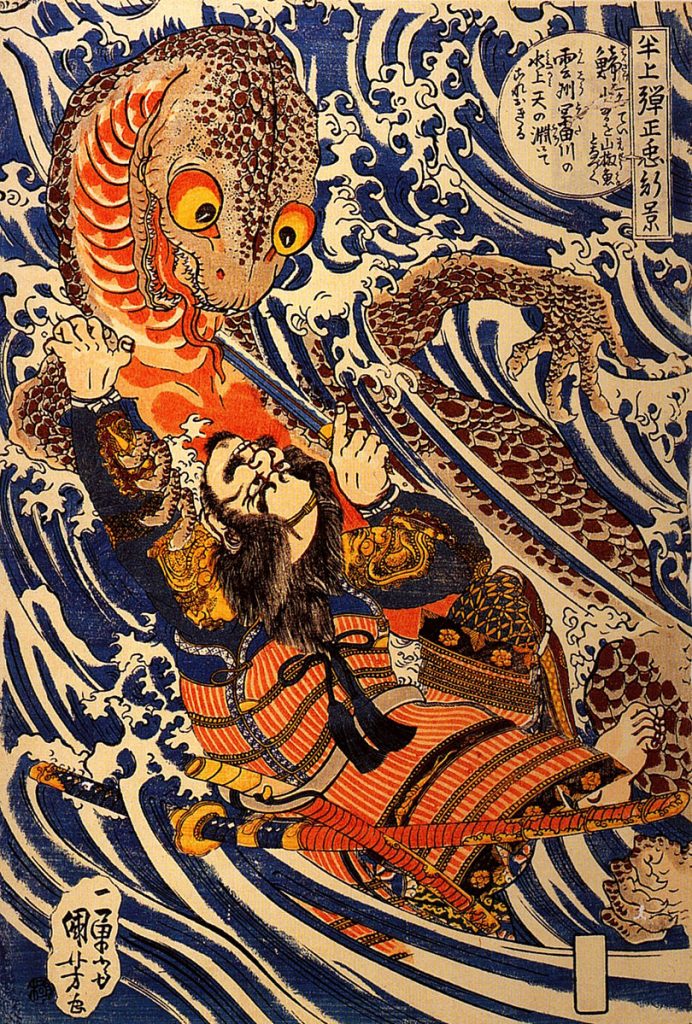

Japan has a rich cultural storytelling history that includes many tales based on monstrous creatures. The Japanese language even has a unique word, ōmagatoki, which refers to the time around dusk when chimimōryō, or mountain and river monsters, attempt to materialize in the human world. In fact, Japanese folklore and mythology is heavily populated by various yōkai, including giant beings whose footprints create vast lakes and ponds, telepathic monkey-like creatures, innocuous spirits that inhabit everyday objects, and beings that secretly cut people’s hair. Looking at these historically legendary yōkai, the origins of the kaijū genre become clearer. For example, the Namazu, or Ōnamazu, might be said to be a proto-kaijū at the intersection of folk beliefs, storytelling, and religion. A giant catfish that lives underground and is usually guarded and restrained with a stone by the thunder god Takemikazuchi, Namazu is said to thrash around wildly and cause earthquakes when the god is away.

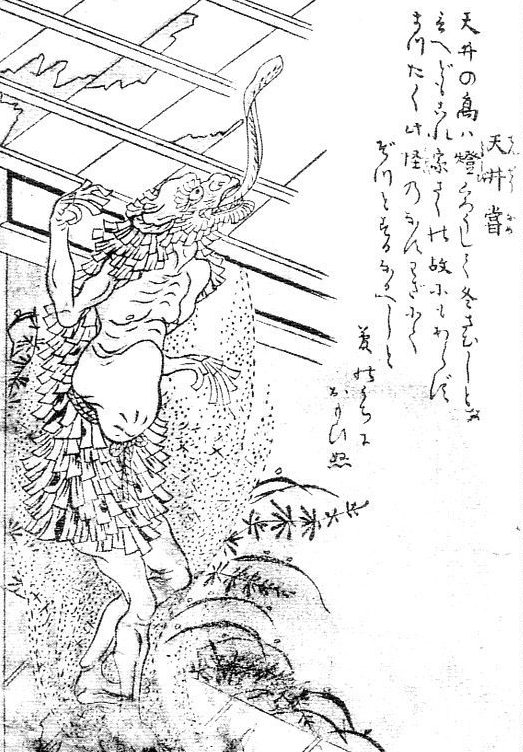

Besides this, Shinto in particular includes many god-like deities who are responsible for various natural elements, such as the sun and rain, and even human endeavours like agriculture and sports. These kami, as well as many others, are directly related to the notion of nature running its course, a theme which is fundamental to the kaijū genre and its focus on the wrath of nature in the face of human exploitation and destruction. Furthermore, Japanese folklore and mythology feature many strange creatures that may serve as inspiration for the modern kaijū film genre. These include the Raijū – a thunder-animal companion to the thunder-god Raijin that varies in depictions of its form, and the Basan – a legendary chicken-like creature that breathes a cold non-burning fire. From these examples, it becomes evident that the human fascination with giant animals, especially reptiles and flying creatures, has endured for centuries. It also likely had a profound influence on the imaginations of kaiju film creators.

Indeed, while the genre continues to evolve, the fears which are represented through these kaijū movie stars can often be traced back to ancient times. Old legends of chimerical animals have been adapted into movies like Sharktopus, suggesting that there is a historical legacy behind many of sci-fi’s favorite and least-favorite movie monsters, no matter how novel the creations may seem. The fear of advancing technology, for example, has been a driving theme of the kaijū genre since before Mechagodzilla, and one that continues to motivate modern franchises like Pacific Rim. In productions that might be said to be variations on the kaijū genre, there can be less focus on the destructive theme of powerful creatures and more emphasis on the idea of connection with the spiritual world. For example, Spirited Away and Avatar: The Last Airbender both beautifully portray the spirit realm by emphasizing the importance of respecting and protecting the spirits closely tied to nature. Such works focus more on kaijū origins in Shintoism and animism.

The true brilliance of yōkai lies in the fact that they are inherently dynamic characters which reflect the constantly evolving anxieties of society. In this sense, yōkai are also not easily definable, and visual depictions of them can differ significantly based on time and context. In fact, the formation of a yōkai is a process that may continue indefinitely, first after one experiences a strange phenomenon, then retold in various tales, and finally represented visually. However, as mentioned, visual representations can vary wildly, especially as stories evolve over time. Keeping this in mind, one can see how yōkai have evolved from spiritual deities to sci-fi mega-monsters. Take, for example, the yōkai known as Hanzaki. A Japanese giant salamander famously able to heal itself after being cut in half if left undisturbed, the Hanzaki would attack and eat livestock or humans if it grew large enough. Legends tell of a local boy who slayed one such monster 10 meters long and 5 meters wide, but who was later plagued by strange phenomena, along with the rest of his village. This led to the fear that the dead Hanzaki had cursed them. Once the villagers built a shrine and began to worship the creature as a god, the spirit was pacified, and the curse was ended. This idea of a (super)natural beast punishing humans for their intervention in nature is one that perseveres in the kaijū film genre, with perhaps the most glaring example being the story of Godzilla.

While not an exact retelling of the Hanzaki tale, the Godzilla formula is based on a similar theme of nature pushing back against the humans who arrogantly impose their desires onto the natural world. The first Godzilla film depicted the monster as the embodiment of radioactive disaster, and this strategic emphasis on humanity’s fears about nuclear radiation was one of the many reasons the film became so successful. Notably, the 1954 film was partly influenced by the Lucky Dragon 5 incident, in which the entire crew of a Japanese fishing boat was exposed to nuclear fallout after US forces tested a thermonuclear weapon nearby with insufficient notice given. Of course, one of the most important events shaping this first Kaijū film was also the recent bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effectively making Japan the first country in the world to ever have experienced, and survived, an apocalyptic disaster. This opened the door to the popularization of apocalyptic themes in science fiction, as well as the kaijū as a symbolic embodiment of nature, since many had great anxieties about the consequences of the bombings on the population and environment. In general, kaijū like Godzilla are so successful as film stars precisely because they reflect the fears of the cultures around them.

Many of the most successful sci-fi films and franchises of all time, including Akira, The Matrix, Ghost in the Shell, and Star Wars also borrow heavily from Japanese beliefs. In these stories, as well as others, the depiction of nature is often linked to spirituality or at least to great power, prompting the characters and the audience to feel a need to respect it. Another popular portrayal of nature in sci-fi films is that of an apocalyptic wasteland, or at least a heavily technologized cityscape which eliminates the presence of nature in populated areas. Science fiction is inherently tied to technology, which is itself tied to the notion that humans could potentially damage or destroy their own accomplishments due to greed and ignorance. As a result, environmental themes are pervasive throughout the sci-fi genre. Japanese folk and religious beliefs often connect the notion of environmental health to spiritual health, and by extension the notion of environmental disaster to spiritual disaster. The theme of apocalypse in science fiction is therefore closely connected to the idea of kami, perhaps most beautifully illustrated in Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke. In a harrowing scene near the end of the film, the forest spirit is shot and decapitated. As ooze explodes from its body and covers the land, it immediately kills anything that it touches. Keeping true to Shinto beliefs about the veneration of nature, this apocalyptic disaster is only reversed when humans respectfully return the head to the forest spirit, who dies and washes over the land to restore and heal nature once more. The direct connection between kami and nature was made explicit when Miyazaki explained:

“In my grandparents’ time, it was believed that kami existed everywhere — in trees, rivers, insects, wells, anything. My generation does not believe this, but I like the idea that we should all treasure everything because spirits might exist there, and we should treasure everything because there is a kind of life to everything.”

– Hayao Miyazaki

So why is the kaijū film genre so successful with Japanese audiences? To put it simply, there is a strong cultural history in Japan that has preserved a plethora of local myths and beliefs, which have then in turn influenced kaijū stories. These stories act as representations or warnings of some of the greatest anxieties that people have about living in and acting against the natural world. But kaijū as a genre is largely successful because of its boundlessness, because there will always be new fears that can be represented through new or evolved kaijū stories. In the first Godzilla film, the prehistoric creature was unleashed by a hydrogen bomb test, but in the latest versions, newer anxieties like climate change are emphasized as more instrumental factors. As societies change around the world, the kaijū film genre will evolve as well, not only because kaijū represent the reaction of nature to humanity and the repercussions of modern advancements, but also because the lifespan of the genre is theoretically infinite. With each new advancement in human technology, there will always be new fears about the consequences of our actions, and there will always be new ways to represent those fears through kaijū, big-screen supernatural embodiments of the ferocity of nature.

Bibliography

Napier, Susan J. “Panic Sites: The Japanese Imagination of Disaster from Godzilla to Akira.” Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 1993, pp. 327–351. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/132643. Accessed 25 June 2021.

Noriaki TAKEMOTO, Takayuki Tatsumi, Full Metal Apache: Transactions Between Cyberpunk Japan and Avant-Pop America, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2006., xxvi+241pp., Studies in English Literature, 2007, Volume 84, Pages 274-280.

Rhoads, Sean, and Brooke McCorkle Okazaki. 2018. Japan’s green monsters: environmental commentary in Kaiju cinema. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1696915.

Tsutsui, William M., and Michiko Itō. 2006. In Godzilla’s footsteps: Japanese pop culture icons on the global stage. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10150454.

[[footnotereferences]]

About the Author

Sofia Sanders is a recent graduate who completed the Global Media and Cultures Master of Science at Georgia Tech with a concentration in Russian. Her Master’s Thesis focuses on the interrelationships within cross-cultural communication, investigating the state of the Russian news media, particularly with regard to corruption, censorship, and bias. Her interest in Speculative Fiction stems from fond childhood memories of Lord of the Rings, as well as her passion for cross-cultural (meaning alien cultures too!) reading and writing.