An essay exploring the folktale selection in the Translating Culture collection

By Sofi Sanders

Like most children, I was fascinated by stories from a young age. I would often ask my parents to read the classic tales associated with a Russian childhood, such as Kolobok, the story of a ball of dough who runs away from a baker but is still eventually devoured by a duplicitous fox. I remember reading this tale over and over in a Russian folktale picture book I owned, long before I had ever heard of the Gingerbread Man and the similar unfortunate end to his story. When I started attending school, I learned about stories from other European traditions and noticed similar patterns across these tales. These were small realizations, like slowly becoming aware that foxes often represented sneaky characters, or that good-hearted people often prevailed over evildoers.

Over time, I also started to read stories from other cultures, including Greek, Spanish, Japanese, and Middle Eastern folktales. The more I read, the more similarities I recognized across the world of myths, a sentiment echoed in Joseph Campbell’s 1949 The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In this canonical work, Campbell explores the idea that mythical tales often share a fundamental story structure across cultures. Of course, each culture certainly demonstrates unique cultural differences, but I was intrigued by the common ideas and themes that connect storytelling around the globe. Though I didn’t think much this at first, I slowly realized that this could be a meaningful revelation based on the fact that humans are, at the most fundamental level, storytelling animals. And, as far as we know, we are the only species that engages in this form of art in order to teach moral and ethical lessons.

Campbell wrote about a “monomyth,” a story structure that was repeatedly seen in tales from various cultures. This monomyth, also called “the hero’s journey,” consists of a hero going on an adventure, being victorious in a decisive crisis, and returning home transformed. While this is a popular story structure, and many story elements do transcend cultures, Campbell’s monomyth leaves little room to explore culturally unique differences demonstrated in stories. Donald Cosentino, a professor of folklore, literature, and African studies, warned that “it is just as important to stress differences as similarities, to avoid creating a (Joseph) Campbell soup of myths that loses all local flavor” (183). Other folklorists have formulated and utilized indices in order to categorize stories based on their types and motifs.

The Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) Index catalogues folktales based on their type, which Thompson defines as “a traditional tale that has an independent existence. It may be told as a complete narrative and does not depend for its meaning on any other tale. It may indeed happen to be told with another tale, but the fact that it may be told alone attests its independence. It may consist of only one motif or of many” (415). A similar index was created by Thompson as well, the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, which catalogues motifs in folktales, defined as “the smallest element in a tale having a power to persist in tradition. In order to have this power it must have something unusual and striking about it” (ibid). Thompson’s index categorizes motifs under umbrella topics, where for example the category of “Unnatural Cruelty” will have within it the entry “Cruel relatives-in-law”, and within that will be the entry “Cruel mother-in-law plans death of daughter-in-law”. This allows for a much more intricate understanding of the interconnections between folktales from various cultures, as these connections are emphasized through the umbrella motif categorizations. Both of these indices are essential tools for folklorists today, and help to illuminate many of the shortcomings of Campbell’s monomyth, as motifs and story types vary widely across cultures. I believe that, while similarities in folktales from around the globe emphasize the core humanity that connects all cultures, the differences between these stories illuminate the ways in which life is different for people around the globe. Being mindful of these differences might help us to understand and learn from one another.

When we started to put together the inaugural edition of HIVEMIND, I couldn’t help but think back on my past experiences and ideas about the intercultural connections demonstrated through folktales. My study concentration and cultural background in Russian allowed me to dive into Russian tales. My co-editor, Will, has a similar concentration in Spanish and found a few Latin American stories to showcase the similarities and differences of folktales within these two cultures. I also realized as I was reading about various cultures and folktale history that Middle Eastern stories, including those from “The Thousand and One Nights” collection, had many similarities to some of the most popular stories around the world. As such, I decided to include an Arabic language version of a folktale in my collection as well. With the cultures chosen, I set out to find some interesting stories that would lend themselves well to the multimedia format of the website. I wanted to be able to visualize and emphasize certain elements of the stories that were culturally specific, as well as demonstrate the parts of the stories that are recognizable across cultures. I included culturally-specific words with translations so as to preserve the meaning of these terms within their cultural context, as well as the illustration of key concepts and plot points via images and gifs to portray the imagery presented in the stories and highlight cross-cultural ideas.

I started with the Russian language stories because I have the most cultural familiarity with them. I wanted to first relay the story of Father Frost, whom I often referred to throughout my multicultural childhood as a “Russian version of Santa Claus,” but who I now recognize as a much more complex character. Unlike cheery old Saint Nick, Ded Moroz (lit. “Grandpa Frost”) was stern and could be very harsh to those who did not respect him. This is demonstrated in the story when he freezes a young girl to death because of her insolence and disrespect. On the other hand, he celebrates another young girl (the main character’s stepsister) who is sweet and respectful to him, showering her with expensive gifts and ensuring her warmth and safety through the winter cold.

As a child, I made the simple connection that both Father Frost and Santa were male figures who represented Christmas and Winter and assumed that they were the same character. However, I now notice some of Ded Moroz‘s interesting particularities, which makes me wonder about the cultural origins of the myth. Particularly interesting to me is the idea that this character serves as a metaphorical warning and simultaneous embrace of the harsh winter weather that is so well-known across Russia. When I first heard this story, I interpreted it to mean that I should always be attentive and considerate to Ded Moroz and to winter in general because, though it may be beautiful and nice, it can quickly turn dangerous. This may sound strange to those who have never lived in cold weather climates, but Russian parents instill in their children a deep respect – as well as fear – of the cold. Going outdoors with wet hair, or without a hat or scarf, is often seen as provoking the cold weather and tempting fate (or Ded Moroz) to teach you a lesson about respecting the power of the cold.

This story also showcased some motifs that are reflected in countless other cultures’ folktales, such as the “talking animal trope” and the connected idea that the talking animals somehow know or understand some deeper truth that humans cannot. It also illustrates the stepmother trope, most famously employed in Disney stories like Cinderella, wherein the stepmother clearly despises and resents her stepdaughter while showering her own daughter(s) with love and gifts. One final note about this story, which I only recently recognized as another motif that repeats across cultures, is that it demonstrates a self-fulfilling prophecy, famously associated with Greek mythology and theater. Although the prophecy is told by a talking dog rather than an oracle, the story is motivated by a prophecy of the unfortunate death of the step-daughter, and, as in Greek classics, the prophecy is only ironically fulfilled as a result of the mother’s actions to prevent it from coming true. Again, this is an example of certain story elements transcending cultural barriers, but it also illustrates the cultural differences that color the use of these various story elements.

The next Russian story I “translated” also centers on a mythical character that I often equated with a Western mythical character: the Witch. The story Baba Yaga (literally Grandma Yaga) unfolds much like the classic children-in-danger-at-a-witch’s-house-in-the-forest trope, most famously demonstrated in the tale of Hansel and Gretel. The Russian version, however, differs in that the children know that they are going to the evil witch’s house and have been sent there on purpose by their wicked stepmother (there’s that trope again!). Luckily, they have already visited their kind grandmother for advice to protect them from the wicked Baba Yaga.

Unlike in many Western cultures, where the witch is often a general archetype without specific characteristics and personality traits, Baba Yaga is a very specific character. She is not just any witch, but the worst and most infamous mythical creature in the woods. Baba Yaga lives in a cabin that, as every Russian child can tell you, stands upon chicken legs. Unlike the unnamed witch in Hansel and Gretel, Baba Yaga does not try to fatten up the children and fool them into being her dinner, rather, she forces them to work at impossible tasks such as filling a tub with holes in it. Again, this part of the story is more reminiscent of Greek mythical tales, as is the fact that Baba Yaga has supernatural powers allowing her to control the Day and Night, as well as the entire animal kingdom and elements of nature. Nature is generally presented in Russian stories as a great power that does not always represent good or evil. Rather, it signifies the occurrence or proximity of something powerful that humans must respect and fear in order to learn or benefit from. If they do not respect it, they will surely die or be otherwise punished for their arrogance. This dichotomous power of nature is another theme that is often present in various cultures’ storytelling, perhaps best exemplified in the might of the Greek gods, who can use their powers over nature for any means they deem necessary, whether helpful or harmful to humans.

The final Russian story also exemplifies the relationship of humans and nature. In The Language of the Birds, the hero learns how to speak with birds and understand what they are saying, but with this knowledge also comes the prophecy that the hero will end up as a king and his own father will be his servant. This leads to the father throwing the hero out of the house and inadvertently launching him on the journey that will see him become king. Again, here we see the self-fulfilling prophecy storytelling technique that transcends culture and time.

Another interesting element of this story is the trope of a young person, usually a boy, who sets out into the woods, jungle, or other wild nature, and winds up learning from and connecting with the animals there. With the skills he learns from the natural world, he is ultimately able to succeed above all measures upon his return to the human world. This trope is perhaps most famously employed in Disney’s retelling of The Jungle Book and similar tales like Doctor Doolittle. This trend pops up across various cultures, including Russian, where a similar figure is known as Doctor Ay-Baleet (literally Doctor Ow-It-Hurts). Though the plot point of a human learning to verbally communicate with animals may be slightly less common and perhaps specific to a few cultures, the mechanism of a human collaborating with animals is quite common across cultures. We see a similar narrative in the Spanish tale The Parrot That Lost Its Tail.

In this first Spanish story, the theme of human-animal collaboration is explored through the use of the parrot as the only known animal that can in any way verbally communicate with humans (in our language). The story leans on this uniqueness of parrots and in this way perhaps bypasses the supernatural trope of direct animal-human communication which we see in Russian stories, though it is of course still stretching the imagination to allow the parrot to tell his human friend the details of his jungle adventures. Regardless, unlike many stories from around the globe, this story emphasizes the deep friendship and collaboration that can exist between humans and animals, and may speak to the respect and admiration for nature and animals that colors Spanish speaking cultures. The ending of the tale sees the parrot and his human friend successfully defeat and kill a jaguar. In doing so, they help not only the parrot, who was in danger of being eaten, but also the human, who can now show off his prized jaguar skin. This element of the story may also be shaped by Latin hunting culture, which takes pride in the killing and displaying of dangerous animals and their pelts. Furthermore, this story demonstrates the culturally-transcendent idea of the dichotomous power of nature, as the main danger in the story is represented by the jaguar and the hero is ultimately the parrot. Readers are left to form their own opinions on nature and animals, having been informed of the potential power, benefits and risks of the natural wilderness. While this ambiguous message about nature is prevalent across cultures, I have noticed that Russian stories tend to paint nature as more (though not exclusively) scary and dangerous, with the famous example being Baba Yaga in the woods. As a result, Russian children are far more aware of the potential risks of venturing into nature than they are of the magical fun that they might have talking to animals.

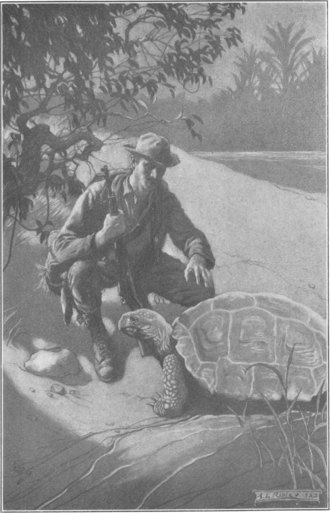

The second Spanish story, taken from the same collection as the first, Horacio Quiroga’s “South American Jungle Tales,” similarly echoes the theme of human-animal collaboration persistent in stories across cultures. The Giant Tortoise’s Golden Rule, however, does not attempt to blur the line between human-animal collaboration and communication, but instead relies on the non-verbal contact between the titular tortoise and his human counterpart in order to establish the idea that animals can in fact be helpful to humans. This story crucially warns readers that humans should not simply take advantage of the natural world, including the animals they stumble upon, but rather that humans may be indebted to animals. Indeed, there may come a time when a human cannot survive without the help of an animal, and not only as a source of sustenance. Another mechanism, which I have labeled as karma (and which might be referred to as Thompson motif C740, or “deed of mercy”), is introduced in this story. This provides an intriguing look into the moral and ethical assumptions in Spanish speaking cultures.

In the beginning of the tale, the man nearly kills the tortoise. However, moved by how badly the animal is injured, he instead chooses to spare it and nurse it back to health. Yet as soon as the tortoise has fully recovered, the man becomes ill and unable to care for himself. In this moment, we first see the inner thoughts of the tortoise, who recognizes the restraint that the man demonstrated in sparing and curing it. The tortoise decides to return the favor by nursing the man back to health. Again, here we see the common cross-cultural theme of animal-human collaboration, as the tortoise collects berries, grasses, and water to heal the man. Unlike many similar stories from other cultures, the man in this story is entirely unaware of the life-saving help that he he has received from the animal until the end of the tale. Also, unlike the first Spanish tale, the animal here is not acting out of self-interest, but out of a feeling of duty and compassion for the man who showed it kindness. This selfless act is repaid by chance. At the end of the tale, the tortoise accidentally delivers the man to his friend, who happens to be the zoo director. As a result, the tortoise receives a comfortable living arrangement there for the rest of its life. This thematic idea of karma, which enables a character to achieve an outcome in line with the morality of their own behavior, is certainly present in other cultures’ storytelling. This is reflected in prophecy-centered stories like Father Frost, where the mother’s terrible treatment of her step-daughter leads to the death of her own daughter. Though karma is a culturally transcendent storytelling element, this tale uniquely combines the ideas of karma and human-animal collaboration. The tortoise acts compassionately towards humans and is also the agent of karma who leaves a significant impact on the human world.

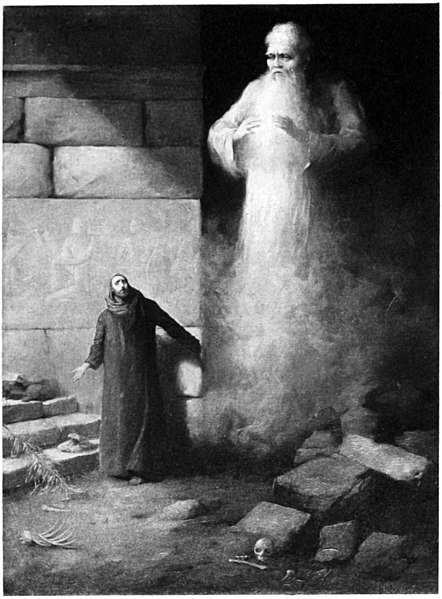

Finally, turning to the Arabic language story, which was chosen from a 1912 translated version of “The Thousand and One Nights” collection, The Story of the Fisherman introduces another storytelling element that is common across cultures: last chance luck. (This folktale also overlaps with Thompson motif N620, “accidental success in hunting or fishing”). What I refer to here as “last chance luck” is commonly referenced in Western culture with the saying “third time’s the charm”, and is a widely used device to build tension and demonstrate supernatural powers in storytelling. This tale sees the fisherman cast his net four times. On the fourth try, he pulls from his net a copper bottle that is now famously associated with a genie, immortalized in the Disney classic, Aladdin. Like the other stories discussed, this one similarly employs and emphasizes the idea of karma in order to motivate the plot, but perhaps the most interesting aspect of this story lies in the ways in which it diverges from the expectations that many Western-influenced readers may have for a story that includes both karma and a genie in a bottle.

Western readers might assume that the fisherman will be granted three wishes and somehow or another achieve worldly success via collaboration with the genie. In this Arabic language story, none of the above occurs. On the contrary, the fisherman is threatened by the genie, denied any wish other than the ability to request how he will be killed, and betrays the genie by trapping him in the bottle. Thus, the story ends with no substantive changes to the fisherman’s level of success in life. While this may seem a bit bizarre when comparing this story to the Westernized movies inspired by the stories in the Arabian Nights collection, when considered in isolation, the story demonstrates many of the same cross-cultural storytelling elements which have been discussed above. For example, the genie is punished by the power of karma. When he is released by the fisherman, he is so angered by his long imprisonment that he decides to kill him; however, he is swiftly betrayed and re-imprisoned because of his unwillingness to spare the man who meant no harm. This tale also employs an interesting version of the dichotomous power of nature theme, if this theme can be expanded to include deities. The genie is cursed for his refusal to embrace faith in Allah and the same force which punishes him also rewards the faith of the fisherman by allowing him to find the copper bottle. Here again, just as in the Russian and Spanish tales, the reader is exposed to both the helpful and harmful powers of the natural and supernatural. In the Arabic language story, the natural and supernatural also overlap with religion, whereas the Russian and Spanish stories do not explicitly state the connection of natural and supernatural powers to God or any other deity. Finally, it is important to note that this story was taken from a collection which is framed as cohesive, with most stories leading directly into other stories or connecting to larger plots which span several stories. For example, this story transitions into another tale and is also referenced later on in the collection. This format of storytelling is quite unique to this collection and is emblematic of the vast differences in storytelling across cultures. Yet, the common themes and motifs explored here demonstrate the transcendence of certain ethical and moral beliefs across cultures and time, connecting the experiences of people from cultures around the world.

When I first started brainstorming this collection and the possible storytelling connections I would be able to make across cultures, I naively narrowed my ideas to include only those stories which I grew up with. I fortunately realized, after collaborating with people from various other cultures, that many common themes transcended cultural boundaries and appeared in very different folktales from very different places. The uniqueness of each culture is clear in this small collection, but all of these stories can be understood by readers from almost anywhere around the globe. Emphasizing the differences between these folktales can help open our eyes to the lessons that we can learn from our respective cultures. Perhaps the biggest takeaway from a review of these folktales is that, no matter the cultural differences that divide many groups of people, there are key commonalities that unite all humans regardless of their background, commonalities which are exemplified via the special skill that belongs only to humans: the art of storytelling.

Works Cited

Campbell, Joseph, 1904-1987, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books, 1949.

Cosentino, Donald J. “African Oral Narrative Traditions” in Foley, John Miles, ed., “Teaching Oral Traditions.” NY: Modern Language Association, 1998.

Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

University of Alberta. Unpacking World Folk-literature: Thompson’s Motif Index, ATU’s Tale Type Index, Propp’s Functions and Lévi-Strauss’s Structural Analysis for Folktales Found Around the World. https://sites.ualberta.ca/~urban/Projects/English/Motif_Index.htm. Accessed May 3 2021.

“Epinglette Kolobok” is licensed under the CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

“Hero’s Journey” is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“Father Frost: Merry Christmas” is in the public domain under the license PD-US-unpublished.

“Baba Yaga” by Viktor Vasnetsov is in the public domain under the license PD-US-unpublished.

“Russia Stamp 1993 No 73.” is in the public domain under the license PD-RU-exempt.

“Ma’aruf the Cobbler and his Wife Fatimah” by Albert Letchford is in the public domain under the license PD-US-unpublished.

© 2021 by Sofia Sanders. All illustrated images included are in the Public Domain under Creative Commons license.

About the Author

Sofi Sanders is an assistant editor of HIVEMIND Magazine, focusing on the visual design of the website as well as the Translating Culture collection and this accompanying article. She is a Russian-American graduate student completing the Global Media and Cultures Master of Science at Georgia Tech with a concentration in Russian. She is currently focusing on the interrelationships within cross-cultural communication, and also investigating the state of the Russian news media, particularly with regard to corruption, censorship, and bias. Her interest in Speculative Fiction stems from fond childhood memories of Lord of the Rings, as well as her passion for cross-cultural (meaning alien cultures too!) reading and writing.